FDA to Drop Ban on Sperm Donations From Gay, Bisexual Men

The Food and Drug Administration is making plans to significantly expand the number of gay and bisexual men who could donate sperm anonymously.

Longstanding agency rules ban anonymous sperm donations by men who acknowledged having sex with other men during the previous five years to reduce the risk of spreading pathogens including HIV, the virus that causes AIDS.

Under a proposal it is drafting, the FDA would eliminate the broad ban and instead adopt more pointed screening questions to assess HIV risk, according to people familiar with the agency’s deliberations.

The proposed changes would also apply to donations of other cells and tissues, such as heart valves and ligaments.

The FDA is planning to finalize its proposal by summer. If the White House approves, the new guidelines could go into effect by the end of this year.

Women whose male partner is infertile or who don’t have a male partner rely on donated sperm to become pregnant. Doctors may inject the sperm directly into a woman’s uterus or use it to fertilize eggs outside of the body, known as in vitro fertilization, or IVF.

IVF and other assistive reproductive technologies now account for some 2%, or about 86,000, of infants born in the U.S. each year, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The ban on sperm donations from men who had sex with other men stemmed from the HIV epidemic in the 1980s. Health authorities were concerned about the accuracy of HIV testing at the time. They put in place the ban to reduce the risk that virus would spread through sperm.

Medical organizations and gay-rights groups have pushed FDA in recent years to ease its rules, saying HIV tests are now more accurate and are enough to keep sperm donation safe combined with other precautions.

Precautions include testing donors at least twice, six months apart, for HIV. Donors must test negative both times before sperm vials are released.

The current policy “is based on outdated thinking and is contrary to evidence-based science, and serves to perpetuate discrimination and stigma,” a coalition of groups including the American Medical Association and nonprofit National Center for Lesbian Rights wrote to the FDA last year.

Changes to the sperm donation guidelines would follow a similar move last year allowing more gay and bisexual men to donate blood.

Like the new blood rules, the sperm-donation changes would replace the wider blanket ban with a series of screening questions to assess an individual’s risk, the people familiar with the FDA’s deliberations said.

Alice Ruby, executive director of the Sperm Bank of California in Berkeley, who has written letters to the FDA urging it to update the donation rules, said “people should be evaluated based on their individual risk rather than their identity.”

Expanding the donor pool could address shortages. Many people who use sperm banks to create their families are gay, lesbian, bisexual or queer. Some seek out donors who are also LGBTQ.

Yet sperm banks have said they turn away applicants because they said they had a male sex partner during the past five years.

Sperm banks have been experiencing shortages of donors, especially donors of color. The Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated the problem as young professionals and university students, who often compose a large portion of prospective donors, left cities.

News

Barron Trump to Step Into Political Arena as Florida Delegate at Republican Convention

It will soon be Barron Trump’s time to step into the political spotlight.

Trump, former President Donald Trump’s youngest child, who will graduate from high school next week and has largely been kept out of the political spotlight, was picked by the Republican Party of Florida on Wednesday night as one of the state’s at-large delegates to the Republican National Convention, according to a list of delegates obtained by NBC News.

“We have a great delegation of grassroots leaders, elected officials and even Trump family members,” Florida GOP chairman Evan Power said. “Florida is continuing to have a great convention team, but more importantly we are preparing to win Florida and win it big.”

Trump’s position as a delegate will be his highest-profile political role thus far.

In a family full of politically involved children, Barron Trump, who turned 18 in March, has retained much more of a private life than his older brothers, Eric Trump and Donald Trump Jr., both of whom will also be Florida at-large RNC delegates, along with Trump’s daughter Tiffany.

He was pulled into political headlines last month at the start of his father’s New York criminal trial related to hush money payments to an adult film star ahead of the 2016 election.

The former president’s attorneys argued that he should be allowed a break from trial to attend Barron Trump’s May 17 high school graduation, which Judge Juan Merchan agreed to allow.

The Trump family will have an outsize impact on Florida’s RNC delegation.

Eric Trump, the delegation’s chairman, joined Power, the state GOP chairman, on a phone call with party leaders Wednesday night.

Donald Trump has won the state twice, including by more than 3 percentage points during his 2020 failed re-election bid, and the state party has largely lined up behind his presidential bid this year even before he has been formally nominated.

The party was put in a difficult position this cycle with Gov. Ron DeSantis also running for the GOP presidential nomination, but even with their home-state governor in the race, Florida party officials signaled they would back Trump.

In September, party leaders voted to remove a loyalty pledge requirement that would have required GOP presidential candidates to support the eventual Republican nominee to be on the state’s March 19 primary ballot. The proposal was supported by Trump but openly opposed by DeSantis’ campaign.

Beyond Trump family members, the Florida GOP approved several of the former president’s top supporters as RNC at-large delegates.

Others include Kimberly Guilfoyle, Donald Trump Jr.’s fiancée; Michael Boulous, Tiffany Trump’s husband; former state Attorney General Pam Bondi, a longtime Trump ally who has run pro-Trump super PACs; longtime Trump adviser Sergio Gor; former Marvel Entertainment Chairman Ike Perlmutter, a prominent Trump donor; and a series of state-level Republican politicians who took the risk of endorsing Trump over DeSantis.

News

House Blocks Greene’s Resolution to Oust Speaker Johnson

Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene has officially started the clock on her doomed effort to hold a referendum on Speaker Mike Johnson’s leadership.

The Georgia firebrand brought up the so-called motion to vacate as privileged, meaning GOP leadership is required to bring it up for a floor vote within two legislative days. It’s the second attempt to depose a speaker within seven months.

House leaders are expected to immediately move forward on a vote to block her effort, according to a person familiar with leadership’s plans.

Greene and her ally in the ouster effort, Rep. Thomas Massie (R-Ky.), opted to move on their resolution after Johnson didn’t move quickly on a slew of their demands, some of which they wanted attached to a Federal Aviation Administration reauthorization bill. Greene had pushed for Johnson to agree to four key demands, including not passing further Ukraine aid and defunding the special counsel probes into Donald Trump in upcoming appropriations bills.

The speaker had largely shrugged off the two hardliners and the House is expected to pass a one-week FAA extension in the afternoon vote.

Johnson hasn’t indicated that any of their asks would be included in a broader reauthorization bill Congress will have to consider later this month.

Many members booed and heckled Greene as she read her resolution on the House floor. She fired back that her colleagues were part of the “uni-party,” a term conservatives use to deride Republicans who work with Democrats.

The upcoming vote to block her effort is referred to as a motion to table, which Democrats are expected to support — helping most Republicans block the attempt to depose Johnson.

So far, Greene and Massie have two other Republicans in their corner: Rep. Paul Gosar (R-Ariz.), who has backed ousting Johnson, and Rep. Warren Davidson (R-Ohio), who has said he will vote with them against tabling the resolution.

Several other Republicans — including Reps. Chip Roy (R-Texas), Scott Perry (R-Pa.) and Andy Biggs (R-Ariz.) — have declined to say whether they would support Greene. Republicans have warned that others could join her; with Democratic support, it gives them an outlet to vent frustrations without actually threatening his speakership.

And a handful of others have stated that they would save Johnson for now, despite despising how Johnson has handled a series of divisive votes for the party. Instead, that group said, they will wait until after the election in November to show their disapprobation.

News

Chris Cuomo: I Am Taking A Regular Dose of Ivermectin, We Were Given Bad Information Early on in COVID

Ex-CNN anchor Chris Cuomo disclosed he is taking the pharmaceutical drug Ivermectin to treat his “long Covid” diagnosis, despite disparaging others who promoted the drug in 2020, stating they “need to be shamed.”

Cuomo, who now works for NewsNation, issued the disclosure during an appearance on Patrick Bet-David’s podcast “PBD.”

While the anchor stated that he stands by his earlier remarks on alternative Covid regimens that differed from the vaccine, he asserted that the US government’s guidance on Ivermectin “was wrong” and that he offered his initial analysis based on alleged facts provided by the government at that time.

Now Chris Cuomo is claiming to be taking Ivermectin, a horse paste that has been proven to have no medical use for treating COVID-19. pic.twitter.com/mms2ZIUMgt

— chris evans (@notcapnamerica) May 8, 2024

“My doctors say I have ‘Long Covid,” he said, later adding that “I’m doing all the protocols”

“I do not fault myself for telling people at the time what the government was giving us as best practices…I am going to tell you something else that is going to get you a lot of hits. I am taking a regular dose, whatever, of Ivermectin,” said Cuomo.

“Ivermectin was a boogeyman early on in COVID. That was wrong. We were given bad information about Ivermectin,” he continued.

“The real question is why?… The entire clinical community knew that Ivermectin couldn’t hurt you. They knew it, Patrick. I know they knew it. How did I know it? Because now I am doing nothing but talking to these clinicians who at the time were overwhelmed but they weren’t saying anything, not that they were hiding anything. But it’s cheap, it’s not owned by anybody and it’s used as anti-microbial and an anti-viral in all these different ways and has been for a long time,” said Cuomo.

The NewsNation host then revealed that his doctor and her family were taking Ivermectin during the pandemic, saying “It was working for them. So they were wrong to play scared on that. Didn’t know it at the time, know it now, admit it now, reporting on it now.”

News

Private US Military Contractor to Take Control of Rafah Border Crossing in Gaza

Israel has committed to the United States and Egypt to restrict its operation in Rafah, which started on Monday, aiming only to deny Hamas authority over the border crossing that connects Gaza with Egypt, and concentrating on the eastern side of the city.

The parties agreed that a private American security company will assume management of the crossing after the IDF concludes its operation. Israel has also pledged not to damage the crossing’s facilities to ensure its continuous operation.

State Department spokesperson Matthew Miller said on Wednesday that he is not aware of Israel agreeing to transfer control of the crossing. The White House also said it was unaware of such an agreement.

Prior to the ground invasion of Rafah, Israel made it clear in talks that the operation’s objective is to exert pressure on Hamas in the hostage negotiations and to harm the crossing’s reputation as a symbol of Hamas power, as it serves as Gaza’s main lifeline.

Israel believes that Hamas’ loss of control over the Rafah crossing would be a significant setback for the group. It will not be able to collect taxes imposed on trucks and goods and will no longer be able to bring in weapons and other items banned from entering Gaza.

The Egyptians and Americans initially opposed any wide-ranging operations by the Israel Defense Forces in Rafah out of fear it would lead to heavy civilian casualties in the densely populated area.

Egyptian officials made clear during the discussions that they opposed an assault on Rafah out of concern that civilians would force their way over the border fence to take shelter against it. According to them, Hamas might try to destroy part of the fence to help large numbers of Gazans to flee.

According to the Gaza Crossings Authority, between 8,000 and 10,000 Gaza Strip citizens have fled to Egypt since the start of the war. Israeli defense officials who spoke with Haaretz said the U.S. made it clear that, should Israel proceed far into Rafah without the express approval of the administration, it faces the prospect of having its access to weapons restricted.

As part of Israel’s efforts to win agreement for a Rafah operation, negotiations have been underway with a private company in the U.S. that specializes in assisting armies and governments around the world engaged in military conflicts. The company has operated in several African and Middle Eastern countries, guarding strategic sites like oil fields, airports, army bases and sensitive border crossings. It employs veterans of elite U.S. Army units.

Under the understandings between the three countries, when Israel has completed its limited operation in the border crossing area, the U.S. company will take responsibility for operating the facility. That includes monitoring goods arriving in the Gaza Strip from Egypt and preventing Hamas from re-establishing control of the crossing. According to the agreement, Israel and the U.S. will assist the company as necessary.

The Egyptians submitted a complaint to Israel on Tuesday regarding IDF troops who had uploaded videos showing the Israeli flag being flown at the Rafah crossing. The Egyptians argued that such a symbolic and public step harms their efforts to downplay the action close to their territory.

News

READ: Michael Avenatti Releases Scathing Statement in Response to Stormy Daniels Testimony Against Trump

Porn actress Stormy Daniels was called to the stand on Tuesday by the prosecution in the New York criminal case against former President Donald Trump.

Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg (D) charged Trump with 34 felony counts for allegedly falsifying business records in an attempt to conceal a $130,000 so-called “hush money” payment to Daniels, who claimed the two had an affair. Trump has pleaded not guilty to all charges and denied Daniels’ allegations.

On Tuesday, Daniels told the jury that she “blacked out” during the alleged sexual encounter with Trump.

“I just think I blacked out. I was not drugged. I was not drunk. I just don’t remember,” Daniels testified. “I told very few people that we had actually had sex, because I felt ashamed that I didn’t stop it.”

Daniels also claimed that there was an “imbalance of power” because Trump was “bigger” than her. She noted that she “was not threatened verbally or physically.”

Trump’s legal team requested a mistrial Tuesday, claiming that during her direct examination, Daniels told a story that differed from her previous public statement.

Todd Blanche, an attorney for Trump, told acting Justice Juan Merchan, “A lot of the testimony that this witness talked about today is way different than the story she was peddling in 2016.”

“She talked about a consensual encounter with President Trump that she was trying to sell … and that’s not the story she told today,” he stated. “But now we’ve heard it. And it is an issue. How can you unring the bell?”

Merchan rejected the request for a mistrial but agreed that Daniels had provided unnecessary details.

During the cross-examination, Trump’s attorney Susan Nucheles asked Daniels, “Am I correct that you hate President Trump?”

“Yes,” she replied.

Following Daniels’ testimony, her former attorney Michael Avenatti posted a scathing statement on X. Avenatti, who had been disbarred and is currently serving time in a federal penitentiary, claimed Daniels had committed the same crime Trump was being accused of in the case.

He explained that he was contacted last year by a producer working on a documentary about Daniels. He had considered participating in the documentary until he learned that Daniels was getting paid for it, calling it “a clear indication to me that the project lacked integrity, would be one-sided, and controlled by Daniels.”

Additionally, Avenatti claimed that the producer told him that Daniels was going to be “secretly paid” to hide the money because “she owed Trump hundreds of thousands of dollars” following a defamation suit.

“Among other things, [the producer] told me that they had fictionally ‘optioned’ the rights to Daniels’ book and then routed the money Daniels demanded through a fabricated ‘trust’ that had been set-up in the name of Daniels’ daughter — all to hide the money from Trump and avoid paying the judgment,” Avenatti wrote.

He added that if the information he was told was accurate, “How can DA Bragg possibly rely on the testimony of Daniels, who is herself guilty of fraud and recently falsifying business records to cover-up a crime (i.e. fraudulent transfer and wire fraud)?”

“Further, will DA Bragg or others be promptly filing criminal charges against Daniels or others involved in this scheme?” Avenatti asked.

The producer did not respond to a request for comment from Just the News.

There are three court orders demanding Daniels pay Trump $560,000 in legal fees.

During her testimony on Tuesday, she told Trump’s legal team that she had “chosen not to pay while it’s still pending.”

Avenatti told the New York Post last month that he would be willing to testify for the defense. He stated that he has been in talks with Trump’s attorneys.

“I’d be more than happy to testify, I don’t know that I will be called to testify,” he told the Post.

Avenatti is currently serving a 19-year jail sentence for extortion, tax evasion, fraud, embezzlement, and other federal offenses.

“There’s no question [the trial] is politically motivated because they’re concerned that he may be reelected,” he told the Post. “If the defendant was anyone other than Donald Trump, this case would not have been brought at this time, and for the government to attempt to bring this case and convict him in an effort to prevent tens of millions of people from voting for him, I think it’s just flat out wrong, and atrocious.”

“I’m really bothered by the fact that Trump, in my view, has been targeted. Four cases is just over the top and I think there’s a significant chance that this is going to all backfire and is going to propel him to the White House,” Avenatti continued. “Depending on what happens, this could constitute pouring jet fuel on his campaign.”

He further claimed that Daniels is “going to say whatever she believes is going to” help her and allow her to put “more money in her pocket.”

Avenatti stated that he wished he never met Daniels.

“If Stormy Daniels lips are moving, she’s lying for money,” he added.

In response to Avenatti’s comments to the Post, Daniels told the news outlet that the disbarred attorney is a “lunatic” and a “scumbag.”

“I was about to say that I also wish I’d never met him but I’m actually glad because I’m the one that helped convict him so he couldn’t steal from even more unsuspecting clients,” Daniels told the Post.

During Tuesday’s cross-examination, Trump’s attorney asked Daniels whether it is true that she is “hiding” her assets to avoid paying the judgment against her. She denied the claim and denied setting up a trust for her daughter.

News

Illegal Migrants Won’t Leave Tent City, Send List of 13 Demands to Dem Mayor

A group of illegal immigrants in Denver is refusing to leave encampments until the city meets its demands.

The migrants published a document with 13 specific demands before they acquiesce to Denver Human Services’ request to leave the encampments and move to more permanent shelters funded by the city.

“At the end of the day, what we do not want is families on the streets of Denver,” Jon Ewing, a spokesman for Denver Human Services, told Fox 31.

The list sent to Mayor Mike Johnston included requests for provisions of “fresh, culturally appropriate” food, no time limits on showers and free immigration lawyers, the outlet reported.

The migrants insisted that if these are not met, they will not leave their tent community.

The current encampment is situated “near train tracks and under a bridge,” Fox 31 noted, adding that it has been there for the last couple of weeks.

Further details of the demands read, “Migrants will cook their own food with fresh, culturally appropriate ingredients provided by the City instead of premade meals – rice, chicken, flour, oil, butter, tomatoes, onions, etc… Shower access will be available without time limits & can be accessed whenever… Medical professional visits will happen regularly & referrals/connections for specialty care will be made as needed.”

The migrants also insisted they get “connection to employment support, including work permit applications for those who qualify,” as well as “Consultations for each person/family with a free immigration lawyer.”

Additionally, the migrants demanded privacy within the shelter once moved there and, “No more verbal or physical or mental abuse will be permitted from the staff, including no sheriff sleeping inside & monitoring 24/7 – we are not criminals & won’t be treated as such.”

The demands were sent following the Denver government obtaining a petition to have the migrants moved, according to the outlet.

Ewing told Fox 31 the city just wants “to get families to leave that camp and come inside,” noting its offer will give migrants “three square meals a day” and the freedom to cook.

He also said the government is willing to work with people to compromise and help them figure out what kind of assistance they qualify for.

Ultimately, Ewing said, the city wants to work with migrants to determine, “What might be something that is a feasible path for you to success that is not staying on the streets of Denver?”

The Denver mayor has been under pressure from the city’s ongoing migrant crisis, making headlines and receiving stiff backlash earlier this year for proposing budget cuts to the city’s government, including cuts to the city’s police force, to fund more money for dealing with the city’s migrant crisis.

News

Teens Expelled from California Catholic School for Alleged ‘Blackface’ Win $1M — It Was Green Acne Medication

Two California teens who were forced to withdraw from an elite Catholic high school over accusations of blackface have been awarded $1 million and tuition reimbursement.

A Santa Clara County jury sided with the teens, identified by the initials A.H. and H.H., on two claims concerning breach of oral contract and lack of due process.

The boys sued Saint Francis High School in August 2020 after photos circulated of them sporting acne treatment masks.

The controversy started when the boys were accused of performing blackface and were ultimately pressured into withdrawing from the prestigious Mountain View school.

‘It was quite clear the jury believed these were innocent face masks,’ attorney Krista Baughman told the San Francisco Chronicle after Monday’s judgement.

‘They are young kids, their internet trail is going to haunt them for the next 60 years. Now they don’t have to worry about that.’

The teens lost on three other claims alleging breach of contract, defamation and a violation of free speech.

The plaintiffs initially sought $20 million when they filed suit in Santa Clara County Superior Court, three years after they and a friend – who attended another school and was not included in the lawsuit – snapped a selfie while donning acne treatment masks.

In the offending photo, the boys’ faces were covered in dark green medication. A photo taken a day earlier revealed that they had tried on white face masks as well.

According to documents reviewed by DailyMail.com, another SFHS student obtained a copy of the photograph from a friend’s Spotify account and uploaded it to a group chat in June 2020.

The photo resurfaced on the same day recent SFHS graduates created a meme pertaining to the murder of George Floyd, which sparked its own outrage and controversy.

The student insinuated that the teens were using ‘blackface’ and deemed the photo ‘another example’ of racist SFHS students, before urging everyone in the group chat to spread it throughout the school community.

On June 4, 2020, Dean of Students Ray Hisatake called the boys’ parents to ask them if they were aware of the photograph.

The parents asserted that the teens had applied green facemasks three years earlier, ‘with neither ill intent nor racist motivation, nor even knowledge of what “blackface” meant,’ according to the suit.

Less than four business hours later, Principal Katie Teekell called H.H’s parents and said the teen was ‘not welcomed back to SFHS.’

When the boy’s father reiterated that his son had not engaged in blackface, Teekell responded that her decision was not based on ‘intent,’ but ‘optics’ and ‘the harm done to the St. Francis community’.

Teekell said H.H. could choose to ‘voluntarily’ withdraw, rather than be expelled, with the incident scrubbed from his student record.

‘At no time did Ms. Teekell, or anyone else from the SFHS administration, offer to investigate the allegations against the boys, or assist in removing the Photograph in any way,’ the lawsuit asserts.

By June 17 the school’s attorney was telling the families the image’s ‘disrespect was so severe as to warrant immediate dismissal’.

The school then backed a protest by parents who used the image as evidence of ‘kids participating in black face (sic) and thinking that this is all a joke,’ according to a Facebook page.

The teens ultimately withdrew on June 19, but H.H. encountered a problem when he attempted to join the football team at his new school.

Despite Teekell’s promise, SFHS was required to disclose that he had switched schools to avoid disciplinary action. This would see him banned from playing sports for a year, per regional rules.

The lawsuit asserted that the principal’s violation of her verbal agreement constituted a breach of oral contract.

H.H. ultimately moved to Utah with his family in order to be eligible to play football during his senior year of high school.

As part of the jury award, SFHS must reimburse the teen’s moving and living costs.

‘This lawsuit is our attempt to redeem our names and reputations, and to correct the record to reflect the truth of what actually happened,’ the boys’ families said in a joint statement at the time.

‘A photograph of this innocent event was plucked from obscurity and grossly mischaracterized during the height of nationwide social unrest.

They claimed SFHS and its leadership had ‘rebuffed’ their attempts to correct the misunderstanding and ‘seemed to have no interest in entertaining the truth’.

Judge Thang Barrett decided against dismissing the suit in January 2021, noting that there was no evidence of an investigation into the matter by administrators.

After Monday’s verdict, SFHS released its own statement.

Representatives for the school said they ‘respectfully disagree with the jury’s conclusion as to the lesser claim regarding the fairness of our disciplinary review process’.

SFHS is now ‘exploring legal options,’ including an appeal.

News

Girl Sues Biden’s Admin After Male Who Competed Against Her Made Rape Threats with No Punishment

A 15-year-old girl from Bridgeport, West Virginia, is suing the Department of Education, claiming there were a series of incidents in which a boy who competed against her and other girls in track and field events made rape threats against her.

According to the girl’s statement, she is currently a ninth-grade student at Bridgeport High School (BHS) who competes in discus, shot put, and the 4 x 100 relay. In sixth through eighth grade, she attended Bridgeport Middle School (BMS), where in seventh grade (the 2021–22 school year), she competed in the 100-meter dash, pole vault, shot put, and discus, and sometimes competed in the 200-meter dash and relay events.

“To my surprise, another BMS student named B.P.J. joined the girls’ track and field team,” she noted. “B.P.J. is almost two years younger than me, and one year behind me in school. Because I know B.P.J.’s older brother from school, I knew at the beginning of the 2021–22 school year that B.P.J. is a male who identifies as a girl.”

She recalled that initially, she was better than the boy in shot put and discus, but by the end of seventh grade, he threw about the same distance in shot put: around 18–20 feet. “In discus, I typically beat B.P.J.: I threw around 40 feet while B.P.J. threw closer to 30 feet. But in the last meet of the 2021–22 season, B.P.J. suddenly threw almost 20 feet farther: 49’ 7”,” she stated.

“By the next school year (2022–23), I could tell that B.P.J. had grown a lot. B.P.J. got taller and threw farther. B.P.J. got a deeper and more masculine voice,” she wrote. In March 2023, B.P.J. finished ahead of the girl at the Connect Bridgeport Invitational in shot put and in discus. In April, B.P.J. beat her at the Pioneer MS Invitational in discus. Later in April, B.P.J. beat her at the Bobcat MS meet in shot put and discus.

“B.P.J.’s athletic records show that B.P.J. beat over 50 different female athletes in the 2021–22 school year, displacing several of the female athletes more than once. These records show that B.P.J. beat over 100 different female athletes in the 2022–23 school year, displacing them almost 300 times. I also lost to B.P.J. on four separate occasions that school year,” the lawsuit states.

“B.P.J. made several offensive and inappropriate sexual comments to me,” she recalled. “At first, it did not occur often, and I tried my best to ignore it. But during my final year of middle school, B.P.J. made inappropriate sexual comments a lot more often; it increased throughout that year; and the comments became much more aggressive, vile, and disturbing. Sometimes B.P.J.’s comments were just annoying, like commenting that I have a ‘nice butt.’ But other times, I felt really embarrassed, and I didn’t want to repeat the gross things B.P.J. said to me. During the end of that year, about two to three times per week, B.P.J. would look at me and say ‘suck my d***.’ There were usually other girls around who heard this. I heard B.P.J. say the same thing to my other teammates, too.”

“B.P.J. made other more explicit sexual statements that felt threatening to me,” she continued. “At times, B.P.J. told me quietly ‘I’m gonna stick my d*** into your p****.’ And B.P.J. sometimes added ‘and in your a**’ as well. … B.P.J. made these vulgar comments towards me in the locker room, on the track, and in the throwing pit for discus and shotput.”

“Most of the time, B.P.J. made these sexual comments at girls’ track practice. Our team walked from Bridgeport Middle School to the High School for track practice, where we would train on the high school track,” she stated. “B.P.J. often popped up beside me as we walked and said these things. Other times, B.P.J. made comments as our team was sitting in the endzone waiting for coaches to get practice going. At least one time, it happened in the girls’ locker room.”

“I reported B.P.J.’s sexual comments to my coach and middle school administrators. Initially, the administrators told me that they were investigating, but we never heard back, and nothing changed. From what I saw, B.P.J. got very little or no punishment for saying things that no other student would get away with,” she concluded.

“I also worry about the little 6th grade girls who are on the same team as B.P.J. right now,” she wrote. “If I were in 6th grade and had to deal with sexual comments from a biological male two years older than me who was changing in the same locker room as me, I wouldn’t even play sports. It wouldn’t be worth it. My younger sister will be a freshman in high school when B.P.J is a senior. She is a good athlete, but she is very shy, and I can’t imagine how she would feel if B.P.J. said those sexual comments to her while they were competing in sports or changing in the locker room. I do not want that to happen.”

Rachel Rouleau of the Alliance Defending Freedom, which is representing the girl, stated:

The Biden administration’s radical redefinition of sex won’t just rewire our educational system. It means young girls will be forced to undress in front of boys in gym class, girls will share bedrooms with boys on overnight school trips, teachers and students will have to refrain from speaking truthfully about gender identity, and girls will lose their right to fair competition in sports. Our client A.C. has already suffered the humiliation and indignity of being harassed by a male student in the locker room and on her sports team. No one else should have to go through that. But the administration continues to ignore biological reality, science, and common sense. This court deserves to hear from those most severely impacted by the administration’s attempt to rewrite Title IX.

News

Georgia Court Agrees to Hear Appeal on Fani Willis Removal from Trump Case

A Georgia appeals court on Wednesday agreed to review a lower court ruling allowing Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis to continue to prosecute the election interference case she brought against former President Donald Trump.

The move seems likely to delay the case and is the second time in as many days that the former president has gotten a favorable ruling that could push any future trials beyond the November election, when he is expected to be the Republican nominee for president. A day earlier, the judge in his Florida classified documents case indefinitely postponed that trial date.

Trump and some other defendants in Georgia had tried to get Willis and her office removed the case, saying her romantic relationship with special prosecutor Nathan Wade created a conflict of interest. Superior Court Judge Scott McAfee in March found that no conflict of interest existed that should force Willis off the case, but he granted a request from Trump and the other defendants to seek an appeal of his ruling from the Georgia Court of Appeals.

That intermediate appeals court agreed on Wednesday to take up the case. Once it rules, the losing side could ask the Georgia Supreme Court to consider an appeal.

Trump’s lead attorney in Georgia, Steve Sadow, said in an email that the former president looks forward to presenting arguments to the appeals court as to why the case should be dismissed and why Willis “should be disqualified for her misconduct in this unjustified, unwarranted political persecution.”

In his order, McAfee said he planned to continue to address other pretrial motions “regardless of whether the petition is granted … and even if any subsequent appeal is expedited by the appellate court.” But Trump and the others could ask the Court of Appeals to stay the case while the appeal is pending.

McAfee wrote in his order in March that the prosecution was “encumbered by an appearance of impropriety.” He said Willis could remain on the case only if Wade left, and the special prosecutor submitted his resignation hours later.

The allegations that Willis had improperly benefited from her romance with Wade resulted in a tumultuous couple of months in the case as intimate details of Willis and Wade’s personal lives were aired in court in mid-February. The serious charges in one of four criminal cases against the Republican former president were largely overshadowed by the love lives of the prosecutors.

Trump and 18 others were indicted in August, accused of participating in a wide-ranging scheme to illegally try to overturn his narrow 2020 presidential election loss to Democrat Joe Biden in Georgia.

All of the defendants were charged with violating Georgia’s Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations, or RICO, law, an expansive anti-racketeering statute. Four people charged in the case have pleaded guilty after reaching deals with prosecutors. Trump and the others have pleaded not guilty.

Trump and other defendants had argued in their appeal application that McAfee was wrong not to remove both Willis and Wade, writing that “providing DA Willis with the option to simply remove Wade confounds logic and is contrary to Georgia law.”

The allegations against Willis first surfaced in a motion filed in early January by Ashleigh Merchant, a lawyer for former Trump campaign staffer and onetime White House aide Michael Roman. The motion alleged that Willis and Wade were involved in an inappropriate romantic relationship and that Willis paid Wade large sums for his work and then benefitted when he paid for lavish vacations.

Willis and Wade acknowledged the relationship but said they didn’t begin dating until the spring of 2022, after Wade was hired in November 2021, and their romance ended last summer. They also testified that they split travel costs roughly evenly, with Willis often paying expenses or reimbursing Wade in cash.

News

US Withholding Bombs from Israel to Stop Rafah Attack: Report

The U.S. withheld certain bombs from Israel to prevent their use in an attack on Hamas battalions in the town of Rafah, according to multiple news reports Tuesday evening.

The news, ironically, came on Israel’s Holocaust memorial day, hours after President Joe Biden told Jews: “Never again.”

The reports confirmed stories that first appeared in Axios earlier in the week. The White House, when asked on Monday and Tuesday, refused to confirm or deny withholding weapons from Israel. Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre insisted merely that U.S. support for Israeli security was “ironclad.”

ABC News reported:

The Biden administration opted to pause a shipment of some 3,500 bombs to Israel last week because of concerns the weapons could be used in Rafah where more than one million civilians are sheltering “with nowhere else to go,” a senior administration official tells ABC News.

…

The decision to pause the shipment and consider slow-walking others is a major shift in policy for the Biden administration and the first known case of the U.S. denying its close ally military aid since the Israel-Hamas war began.

…

More than half of the shipment that was paused last week consisted of 2,000-pound bombs. The remaining 1,700 bombs were 500-pound explosives, the official said.

The Times of Israel also reported:

The Biden administration confirms reports that it held up a shipment last week of 2,000 and 500-pound bombs that it fears Israel might use in a major ground operation in Rafah.

This is the first time since October 7 that the US has held up a weapons shipment earmarked for Israel.

Washington adamantly opposes a major offensive in the southern city of Gaza, convinced that there is no way for Israel to conduct one in a manner that would ensure the safety of the over million Palestinians sheltering there.

Israel launched an offensive in Rafah on Monday, after Hamas attacked a border crossing over the weekend, killing four Israeli soldiers, and refused to agree to a ceasefire and hostage deal. Israel took the Rafah border crossing and the Philadelphi corridor, a road running along the Egyptian border that is a key strategic point to prevent smuggling.

Fox News’ Jacqui Heinrich asked Jean-Pierre how U.S. support for Israeli security could be “ironclad” if the Biden administration were withholding some weapons from Israel. Jean-Pierre said that two things could be true at once.

Critics of Biden’s decision have argued that withholding weapons that Congress has already authorized, absent any finding of human rights violations by Israel, is unconstitutional and violates the Impoundment Control Act of 1974.

News

RFK Jr: A Worm Ate Part of My Brain

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said doctors told him a parasite ate part of his brain, after experiencing memory loss and brain fog in 2010.

The New York Times reviewed a deposition of Kennedy from 2012 that detailed his experience with his symptoms and the dead parasite. The Times reported that Kennedy started dealing with memory loss and mental fogginess in 2010, prompting concerns from a friend that the now-presidential candidate may have had a tumor.

Kennedy gave the 2012 deposition during divorce proceedings from his second wife, Mary Richardson Kennedy. Kennedy discussed his symptoms in the deposition because he argued his cognitive struggles in relation to the situation had diminished his earning power, according to The Times report.

Several doctors who had first concluded Kennedy had a tumor found a dark spot on his brain scans, The Times reported.

However, just as he was packing up to have surgery and remove the tumor, he said in the deposition that another doctor called him and told him he believed Kennedy instead had a dead parasite in his brain.

The doctor told him he believed the spot on the brain scan “was caused by a worm that got into my brain and ate a portion of it and then died,” Kennedy reportedly said in the deposition.

The Times also reported that around the same time as the parasite, Kennedy suffered from mercury poisoning that likely came from eating too much fish, according to the deposition. Mercury poisoning can lead to some neurological disturbance and issues with memory, among other symptoms, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

“I have cognitive problems, clearly,” he said in the deposition, according to The Times. “I have short-term memory loss, and I have longer-term memory loss that affects me.”

Kennedy launched an independent bid for the White House last year after failing to gain momentum in the Democratic primary against President Biden. Age and health concerns have been listed as some of the top worries for voters headed into the election season, as Biden, 81, and former President Trump, 77, remain the two front-runners for November.

Kennedy, 70, has also called on Biden to prove he has the “mental acuity” to handle another term in the White House.

When reached for comment on the story, a spokesperson for Kennedy’s campaign said the presidential candidate contracted a parasite while traveling.

“Mr. Kennedy traveled extensively in Africa, South America, and Asia in his work as an environmental advocate, and in one of those locations contracted a parasite. The issue was resolved more than 10 years ago, and he is in robust physical and mental health,” the campaign said.

“Questioning Mr. Kennedy’s health is a hilarious suggestion, given his competition.”

According to an interview with The Times this winter, Kennedy said he has recovered from the memory loss and fogginess and had no other aftereffects from the parasite. He also said that he did not require treatment for it.

Kennedy said in the interview that after receiving the 2010 call about the parasite, doctors concluded that the cyst on the brain they found had parasite remnants. He said he did not know what kind of parasite it was or where he may have contracted it.

News

WATCH: Boeing Plane Makes Emergency Landing After Gear Failure

A FedEx Airlines cargo plane was forced to land in Turkey without the use of its front landing gear on Wednesday morning, May 8, the Turkish transport ministry said.

Fedex Express Flight 6268, a Boeing 767, was flying from Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport to Istanbul Airport when it informed the Turkish traffic control tower that its landing gear failed to open. Airport rescue and fire teams prepared the runway and the tower instructed the plane’s crew to proceed with landing.

Video of the landing, obtained from Reuters, showed sparks and smoke coming from the front of the plane as it scraped along the runway before coming to a stop. The plane was subsequently doused with firefighting foam.

No one was injured, the ministry said.

The landing video shows the front wheels were initially deployed but appeared to fail to lock into place. They were not used during the landing as the body of the plane made contact with the runway. The aircraft managed to remain on the runway during the landing.

Watch:

WATCH: Terrifying moment Boeing FedEx plane skids along runway as landing gear fails – Location: Istanbul Airport, Turkey

— Insider Paper (@TheInsiderPaper) May 8, 2024

The runway was temporarily closed to air traffic, but traffic on other runways continued without any interruption, said airport operator IGA, Reuters reported.

Authorities are investigating the incident, a Turkish Transport Ministry official said. It gave no reason for the failure.

The Boeing 767 is a nearly 10-year-old freighter. It is one of the most common cargo planes and uses a model dating back to the 1980s.

FedEX said in a statement to Reuters that it was coordinating with the investigation and would “provide additional information as it is available.”

Manufacturers are not typically involved in the operation or maintenance of aircraft after they enter service.

Boeing has remained under intense media scrutiny following a series of incidents with their aircraft in recent months.

News

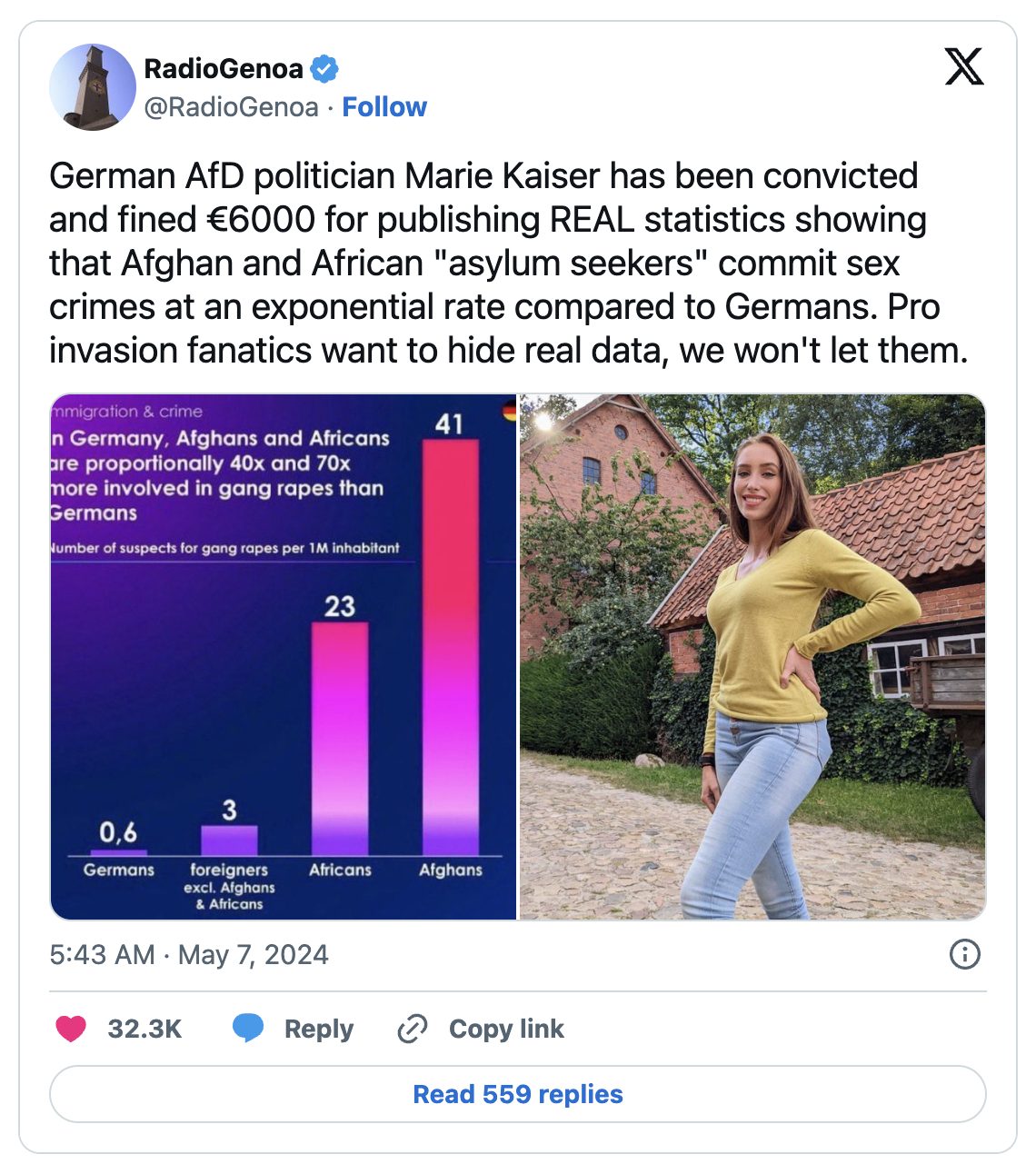

German Politician Convicted of Hate Crime for Sharing Migrant Rape Stats

A right-wing politician in Germany has been convicted of a hate crime and fined thousands of dollars for sharing statistics about the disproportionate number of gang rapes committed by immigrants, specifically Afghan nationals, and for questioning whether multiculturalism means accommodating rape culture.

Marie-Thérèse Kaiser is a member of the right-leaning Alternative for Germany. The 27-year-old women’s safety advocate and former model serves as the party’s only representative in the Rotenburg district council.

While campaigning during the 2021 federal election, Kaiser posted on social media, “Afghanistan refugees; Hamburg SPD mayor for ‘unbureaucratic’ acceptance; Welcoming culture for gang rape?”

The German newspaper Junge Freiheit reported that Kaiser was responding in August 2021 to socialist Hamburg Mayor Peter Tschentscher’s announcement that he would take in 200 Afghan workers. Kaiser was evidently concerned about what impact the new cohort might have on local culture and safety.

Her post was reportedly accompanied by a graphic indicating that Afghan and African asylum seekers “are proportionally 40x and 70x more involved in gang rapes than Germans,” citing government statistics.

The then-AfD candidate cited the statistics to justify her concern over uncontrolled immigration and the possibility of rape by “culturally alien masses.”

Background

Mass immigration to Germany from Middle Eastern nations such as Afghanistan has coincided in recent years with a massive spike in violent crime, including rape.

The Pew Research Center indicated that between 2010 and 2016, Germany accepted over 670,000 refugees and 680,000 non-refugee immigrants. Of the roughly 1.35 million immigrants who flooded into Germany during that period, an estimated 850,000 were Muslims.

A government-commissioned study revealed in early 2018 that there was a 10.4% increase in violent crime at the height of the immigration crisis overseen by former German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who had circumvented EU rules and effectively opened the union’s doors to immigrants from Syria and other oriental states. Deutsche Welle reported that 90% of this violent crime increase was attributable to immigrants, predominantly males between the ages of 14 and 30.

Despite altogether amounting to less than 2% of the overall population at the time, the BBC indicated that over 10% of murder suspects and 11.9% of sex offenders were asylum seekers and refugees in 2017.

The situation has not improved.

Reuters reported last month that the number of criminals with non-German backgrounds continues to climb. In 2023, there was a 5.5.% increase in overall crime and a 13.5% increase in the number of suspects with foreign backgrounds.

“What the AfD has warned about for years can no longer be hidden … new crime statistics have triggered a debate on ‘foreigner crime,'” said Richard Graupner of the AfD in Bavaria.

Imported criminality has not only victimized countless Germans but created horrible new customs.

New Year’s Eve, for instance, appears to have become an annual night of immigrant riots and gang assaults on German women. Blaze News previously reported that two-thirds of the rioters detained in the most recent explosion of New Year’s violence were non-citizens, including 27 Afghans and 21 Syrians.

German Interior Minister Nancy Faeser stated in the aftermath on Jan. 4, “Good politics must clearly state what is happening: In major German cities we have a problem with certain young men with a migrant background who despise our state, commit acts of violence and are hardly reached by education and integration programs.”

Outrage over this imported phenomenon has coincided with the rise of the right-leaning AfD party, which has been critical of the country’s immigration policies.

The BBC noted that various high-profile incidents, such as the brutal rape and murder of 19-year-old medical student Maria Ladenburger by an Afghan criminal in 2016, “helped boost the country’s far right.”

German officials appear to have instead treated the AfD as the problem, harassing and censoring party members. With the AfD polling second nationally and state elections scheduled for later this year, there have even been discussions of banning the party outright.

Free speech ends where inconvenience begins

Kaiser was reportedly charged and convicted with incitement to hatred after raising concerns about a very real problem gripping the nation. She indicated in February that she had appealed the ruling and was scheduled to appear in court in May.

“Simply naming numbers, dates and facts is to be declared a criminal offense just because the establishment does not want to face reality,” she wrote on X. “I will not allow myself to be silenced.”

A court in Lower Saxony upheld the guilty verdict Monday.

The court was unmoved by Kaiser’s argument that freedom of expression in politics, particularly in electoral campaigns, must enjoy special latitude in the spirit of democracy. According to Lower Saxony’s local news outlet, the presiding judge stated, “Freedom of expression ends where human dignity begins.”

Kaiser, identified by the judge as an “exemplary defendant” during her sentencing, must now pay a fine of over $7,000.

Kaiser, who indicated on Instagram that the courtroom was packed full of supporters along with her parents, said of the verdict, “The whole world is amazed at this decision by the German courts. After even Elon Musk took up my case, I received numerous letters from supporters and press inquiries.”

View this post on Instagram

The politician was referencing Musk’s Monday response in which he wrote, “Are you saying the fine was for repeating accurate government statistics? Was there anything inaccurate in what she said?”

“My trust in the German constitutional state was once again severely shaken yesterday, but all the letters give me courage and give me confidence,” added Kaiser.

News

Illegal Immigrant Jose Ibarra Indicted for the Murder of Laken Riley

Laken Riley’s suspected killer has been officially charged with the 22-year-old’s nursing student’s murder.

Jose Antonio Ibarra, an undocumented immigrant from Venezuela, was indicted on 10 counts by a grand jury in Georgia on Tuesday.

The 26-year-old is also accused of peeping through a window to spy upon a staff member at the University of Georgia on the same day he allegedly killed Riley, as first reported by Fox News.

Riley was beaten to death while she was out for a run on the campus in Athens on February 22.

The indictment claims Ibarra inflicted blunt-force trauma to her head and ‘asphyxiating her in a manner unknown to jurors.’

It also states that Ibarra ‘seriously disfigured her head by striking her head multiple times with a rock.’

Ibarra is charged with malice murder, kidnapping with bodily injury, aggravated assault with intent to rape, aggravated battery, obstructing or hindering a person from making a 911 call, tampering with evidence and acting as a peeping Tom.

He allegedly went inside one of the university’s apartment complexes ‘for the purpose of becoming a peeping tom in that he did peep through the window and spied upon and invaded [the employee’s] privacy.’

Riley’s body was found the same day on campus in a forested area near Lake Herrick that includes trails popular with runners and walkers.

Ibarra crossed into El Paso, Texas, in September 2022 but had been released from a detention center due to a lack of space.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement said he had previously been arrested in NYC.

Police say he concealed a jacket and gloves that were evidence to the alleged murder.

Riley studied at the University of Georgia through the spring of 2023 before transferring to Augusta University’s College of Nursing, according to a statement from the University of Georgia, which does not have a nursing program itself. She remained active in the sorority she joined at the University of Georgia.

The killing shocked Riley’s fellow students in Athens, where more than 41,000 attend UGA and another 210 are enrolled in the medical program where Riley studied nursing.

The nursing student became he face of immigration reform for many conservatives in the days since she was killed.

At the State of the Union address, president Joe Biden held up a pin with Riley’s name on it as Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene shouted from the gallery: ‘Say her name!’

Hours after Riley was slain, Athens homicide detectives pulled a photo from a surveillance camera of a potential suspect who wore a distinctive Adidas hat, according to a federal affidavit obtained by The Associated Press.

That eventually led them to an off-campus apartment complex where they searched the grounds and a Dumpster nearby and began to piece together details about Ibarra.

Ibarra shared the apartment with his brother Diego, who is accused of possessing a fake green card after he handed it to police as they hunted for the suspect.

Federal authorities found that Diego has ties to the Venezuela-based gang Tren de Aragua, a violent gang that has been trying to gain a foothold in the US.

Homeland Security Investigators found photos of Diego flashing the gang’s hand signals online, along with identifying tattoos like stars, clocks, trains, weapons and crowns.

More pictures of him with firearms were found online even though illegal immigrants in the US are not legally allowed to own guns.

Diego Ibarra entered the country illegally in April 2023 and was arrested five months later with no license or insurance while driving at 80mph in a 40mph zone and drinking a can of Bud Light.

‘I opened the driver’s door and ordered him to step out of the vehicle, but he turned and began reaching inside of the vehicle, so I forcibly pulled him out,’ the investigating officer wrote.

‘The driver struggled and was brought to the ground, where there was a short struggle to handcuff him.’

Days later, police were called to a domestic disturbance at his apartment but did not arrest him.

Both brothers were cited on October 27 for allegedly stealing more than $200 from an Athens Walmart.

And Diego allegedly returned to steal more items on December 8, earning himself a two-year ban from the store.

UGA Police Chief Jeffrey Clark told reporters that officers searched Jose Ibarra’s apartment in Athens and evidence shows that he acted alone.

‘He did not know her at all. I think this is a crime of opportunity where he saw an individual and bad things happened,’ Clark said.

News

Andrew Tate Sued by 4 British Women Over Rape and Abuse Claims

Andrew Tate has been sued by four British rape accusers including one who claims the disgraced influencer choked her until her eyes started to bleed.

The highly controversial social media star was served his civil proceedings papers at his home in Romania, says the alleged victim’s lawyer.

McCue Jury and Partners said the women are looking to bring Tate, 37, in front of the High Court in the UK.

The law firm said all four women allege Tate raped and assaulted them and are seeking “damages for injuries they suffered as a result”.

They have also made an order to preserve their anonymity “to protect them from harm and harassment by Tate, his

associates, and followers”, claims a McCue Jury and Partners press release.

At the time of the alleged crimes, three of the women went to the police but the Crown Prosecution Service did not bring a charge after a four-year investigation.

A claimant in the latest proceedings said: “We are very pleased that the court has issued our claim, and the case is progressing.

“We only wish that the police had taken proper action when we made our complaints almost ten years ago.

“We are determined to bring Andrew Tate to justice, and this is a major step towards that goal.”

One of the alleged attacks included the 37-year-old “choking them until blood vessels burst in their eyes, beating them with a belt, and raping them numerous times and coercively controlling them”.

One woman even claimed he texted her: “I love raping you.”

Matthew Jury, a solicitor at McCue Jury & Partners, said back in 2023 he was confident the alleged victims could sue Tate.

He said: “We know he is a wealthy individual.

“Depending on the country in which assets are located, UK judgements are enforceable abroad.”

A spokesperson for Andrew Tate said: “The accusations by these four women are demonstrably false and vehemently denied.

“Andrew’s legal team will be vigorously defending him against these allegations.”

The press release also claims the number of female victims of Tate and his brother’s alleged crimes is now up 14.

The former kickboxer is already awaiting trial in Romania on charges of human trafficking and forming a criminal gang to exploit women – allegations which he denies.

Tate, alongside his controversial brother Tristan, have been accused of at least 10 allegations of rape and sexual assault in the past.

They have denied them all.

As well as the four Brits, Andrew and Tristan are also accused of recruiting women on social media platforms and luring them to their villa on the outskirts of Bucharest.

Both men are alleged to have pretended to fall in love with the women before getting them to work for their business and making them perform sexual acts on webcams.

Two Romanian female suspects – model Georgiana Naghel and former cop Luana Radu – were also formally charged.

The four were released on house arrest in August last year.

News

Female Darts Player Forfeits Tourney After Getting Matched Up Against Man

A British female darts player forfeited a quarterfinals tournament match after being slated to face a biological male.

Deta Hedman refused to continue playing in the Denmark Open over the weekend after she advanced to the quarterfinals, where she was pitted against Noa-Lynn van Leuven, a biological man who identifies as a woman. Hedman later denied rumors that she backed out of the competition because of illness.

“No fake illness I said I wouldn’t play a man in a ladies event,” Hedman posted on X, according to Fox News. “This subject causing much angst in the sport I love. People can be whoever they want in life but I don’t think biological born men should compete in Women’s sport.”

The British darts player declined to take any compensation over her decision to forfeit the tournament.

The World Darts Federation (WDF), which organized the Denmark Open, allows biological men to compete in women’s competitions if they “submit documentation from a medical practitioner that gender reassignment has been ongoing for at least one year,” according to WDF guidelines.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC), which sets the rules followed by the Darts Regulation Authority, sets the testosterone level of a transgender competitor wishing to compete against women at 10 nanomoles per liter for at least 12 months. The IOC also states that one cannot have changed his gender identity for at least four years prior.

Van Leuven, 27, began identifying as a woman at the age of 16. The Dutch darts player’s inclusion in women’s competition has roiled players and fans.

Two of van Leuven’s fellow Dutch players quit the national team in protest in March after van Leuven won two titles, one against men and another against women, within one week.

Biological men participating in women’s competitions have upended multiple sports. Some of the most heated reactions have stemmed from incidents in which female athletes have been injured by transgender players.

Earlier this year, the high school girls’ basketball team for Collegiate Charter School of Lowell in Massachusetts forfeited a game at halftime after a number of its players were reportedly injured by a biological male playing on the other team for KIPP Academy.

Collegiate said in a statement about the forfeit that its girls “feared getting injured and not being able to compete in the playoffs.” The school went on to reiterate “its values of both inclusivity and safety for all students.”

News

Trump Classified Documents Trial Suspended Indefinitely

U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon has indefinitely suspended former President Donald Trump’s classified documents trial.

The move had been widely anticipated for some time and marks perhaps the greatest legal victory in Trump’s struggle against his four major indictments. The trial was previously scheduled to take place on May 20.

Cannon gave her reasoning as respecting Trump’s right to due process and the public’s interest in the “fair and efficient administration of justice.”

BREAKING: Judge Cannon indefinitely postpones Trump’s Mar-a-Lago classified docs case pic.twitter.com/D7tKs8cMma

— Hugo Lowell (@hugolowell) May 7, 2024

Special counsel Jack Smith had urged Cannon to hold the trial in July and laid out his case earlier this month. Trump’s team argued that the trial should be held after the November election or after August at the earliest.

Cannon partially justified the delay as needed in order to comply with the Classified Information Procedures Act, which all cases involving classified documents must abide by.

“The Court also determines that finalization of a trial date at this juncture—before resolution of the myriad and interconnected pre-trial and CIPA issues remaining and forthcoming—would be imprudent and inconsistent with the Court’s duty to fully and fairly consider the various pending pre-trial motions before the Court, critical CIPA issues, and additional pretrial and trial preparations necessary to present this case to a jury,” Cannon wrote.

Though not his first official indictment, the classified documents case was the first legal battle with Trump to go public, after FBI agents raided his Mar-a-Lago compound on Aug. 8, 2022.

The search came as a shock to many and represented the first major legal challenge to Trump since leaving office, coming nearly a half year before his first indictment. He was indicted on 40 charges one year after the search.

Trump is accused of mishandling classified documents from his administration, taking them to his private residence after leaving office, and being uncooperative with government officials trying to retrieve them.

News

MTG Offers to Cancel Planned Vote to Remove Johnson — Her List of Demands

Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) has named her price for backing down on her threat to call a vote on Speaker Mike Johnson’s removal, Politico reported.

In a nearly two-hour long meeting yesterday requested by Greene to explore potential off-ramps, the MAGA firebrand and allied Rep. Thomas Massie (R-Ky.) outlined several policy demands they are seeking before calling off their plans.

They include, according to people familiar with the talks:

- No further aid for Ukraine;

- A return to the “Hastert Rule,” meaning no legislation is brought to a vote without support from a majority of the House majority;

- Defunding the special counsel probes into former President Donald Trump in upcoming appropriations; and

- Enforcement of the “Massie Rule,” whereby government funding is automatically cut across the board if no superseding agreement is reached before a set deadline.

They’ll meet again today at 12:30 p.m. in hopes of finding a detente. Spokespeople for Greene and Johnson declined to comment on their discussions, but the speaker struck a conciliatory note after yesterday’s meeting, sympathizing with Greene and pledging to “keep this team together.”

Make no mistake, though, the pressure for Republican party unity in an election year is weighing on Greene, who is battling exasperated GOP colleagues and skepticism from the party’s unquestioned leader, Trump.

Johnson could be in a position to grant at least some of Greene’s asks. Since this Congress has effectively finished passing controversial, must-do items such as funding the government, raising the debt ceiling and extending surveillance authorities, Johnson can probably stick to the Hastert Rule (named for former, now-disgraced speaker Dennis Hastert).

Democrats agreed to a version of the Massie Rule during last year’s spending talks with then-speaker Kevin McCarthy — so Johnson could probably go there as well.

On Ukraine, Congress just sent Kyiv $60 billion in aid — enough to last through the year by most estimates, though Greene might also want to strike an expected nine-figure aid authorization in the annual Pentagon policy bill that’s expected to move later this year.

But defunding special counsel Jack Smith’s Trump investigations could be much trickier. Front-line Republicans in the past have balked at such demands, to say nothing of Democrats. If Greene is expecting Johnson to put up a fight on a much-anticipated September continuing resolution, that would be a recipe for a federal shutdown just weeks before the election.

The two sides don’t have a deal yet — and might never get one — but it’s clear temperatures are dropping. A handshake solution, after all, is in the interest of both parties: It would spare Johnson a risky vote where he’d be relying on the generosity of Democrats to save his gavel.

And for Greene, her relationship with Trump and his inner circle is on the line, we’re told. The former president “could not have been clearer,” one person close to him said last night, in signaling that he isn’t interested in any more intraparty drama this election season.

News

TikTok Sues to Block US Law Seeking Sale or Ban of App

TikTok and its Chinese parent company ByteDance sued in U.S. federal court on Tuesday seeking to block a law signed by President Joe Biden that would force the divestiture of the short video app used by 170 million Americans or ban it.

The companies filed their lawsuit in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, arguing that the law violates the U.S. Constitution on a number of grounds including running afoul of First Amendment free speech protections. The law, signed by Biden on April 24, gives ByteDance until Jan. 19 to sell TikTok or face a ban.

“For the first time in history, Congress has enacted a law that subjects a single, named speech platform to a permanent, nationwide ban,” the companies said in the lawsuit.

The lawsuit said the divestiture “is simply not possible: not commercially, not technologically, not legally. … There is no question: the Act (law) will force a shutdown of TikTok by January 19, 2025, silencing the 170 million Americans who use the platform to communicate in ways that cannot be replicated elsewhere.”

The White House has said it wants to see Chinese-based ownership ended on national security grounds but not a ban on TikTok. The White House and Justice Department declined to comment on the lawsuit.

The lawsuit is the latest move by TikTok to keep ahead of efforts to shut it down in the United States as companies such as Snap and Meta look to capitalize on TikTok’s political uncertainty to take away advertising dollars from their rival.

Driven by worries among U.S. lawmakers that China could access data on Americans or spy on them with the app, the measure was passed overwhelmingly in Congress just weeks after being introduced. TikTok has denied that it has or ever would share U.S. user data, accusing American lawmakers in the lawsuit of advancing “speculative” concerns.

Representative Raja Krishnamoorthi, top Democrat on a House committee on China, said the legislation is “the only way to address the national security threat posed by ByteDance’s ownership of apps like TikTok.”

“Instead of continuing its deceptive tactics, it’s time for ByteDance to start the divestment process,” he said.

The law prohibits app stores like Apple and Alphabet’s Google from offering TikTok and bars internet hosting services from supporting TikTok unless ByteDance divests TikTok by Jan. 19.

The suit said the Chinese government “has made clear that it would not permit a divestment of the recommendation engine that is a key to the success of TikTok in the United States.” The companies asked the D.C. Circuit to block U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland from enforcing the law and says “prospective injunctive relief” is warranted.

According to the suit, 58% of ByteDance is owned by global institutional investors including BlackRock, General Atlantic and Susquehanna International Group, 21% owned by the company’s Chinese founder and 21% owned by employees – including about 7,000 Americans.

Tensions Over Internet and Technology

The four-year battle over TikTok is a significant front in the ongoing conflict over the internet and technology between the United States and China. In April, Apple said China had ordered it to remove Meta Platforms’ WhatsApp and Threads from its App Store in China over Chinese national security concerns.

TikTok has spent $2 billion to implement measures to protect the data of U.S. users and made additional commitments in a 90-page draft National Security Agreement developed through negotiations with the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), according to the lawsuit.

That pact included TikTok agreeing to a “shut-down option” that would give the U.S. government the authority to suspend TikTok in the United States if it violates some obligations, according to the suit.

In August 2022, according to the lawsuit, CFIUS stopped engaging in meaningful discussions about the agreement, and in March 2023 CFIUS “insisted that ByteDance would be required to divest the U.S. TikTok business.” CFIUS is an interagency committee, chaired by the U.S. Treasury Department, that reviews foreign investments in American businesses and real estate that implicate national security concerns.

In 2020, then-President Donald Trump was blocked by the courts in his bid to ban TikTok and Chinese-owned WeChat, a unit of Tencent, in the United States. Trump, the Republican candidate challenging the Democrat Biden in the Nov. 5 U.S. election, has since reversed course, saying he does not support a ban but that security concerns need to be addressed.

Biden could extend the Jan. 19 deadline by three months if he determines ByteDance is making progress. The suit said the fact that Biden’s presidential campaign continues to use TikTok “undermines the claim that the platform poses an actual threat to Americans.” Trump’s campaign does not use TikTok.

Many experts have questioned whether any potential buyer possesses the financial resources to buy TikTok and if China and U.S. government agencies would approve a sale.

To move the TikTok source code to the United States “would take years for an entirely new set of engineers to gain sufficient familiarity,” according to the lawsuit.

News

Boy Scouts Changes Name After 114 Years to ‘Boost Inclusion’ Scouting America

Boy Scouts of America is changing its name for the first time in its 114-year history in a bid to ‘boost inclusion’.

The Texas-based organization is set to become Scouting America as it hopes to improve participation amid flagging membership.

The historic change is the latest in a series designed to take the troop into the 21st century, including allowing gay youth and welcoming girls throughout its ranks.

It comes as the organization is emerging from bankruptcy following a flood of sexual abuse claims.

‘In the next 100 years we want any youth in America to feel very, very welcome to come into our programs,’ Roger Krone, who took over last fall as president and chief executive officer, said in an interview before the announcement.

The announcement came at its annual meeting in Florida on the fifth anniversary of the organization welcoming girls into Cub Scouting.

Boy Scouts of America began allowing gay youth in 2013 and ended a blanket ban on gay adult leaders in 2015.

In 2017, it made the historic announcement that girls would be accepted as Cub Scouts as of 2018 and into the flagship Boy Scout program – renamed Scouts BSA – in 2019.

Eagle-eyed South Park fans have since come forward to suggest that the cartoon may have predicted the Scouts’ move towards progression.

One episode shows the characters attend their first ever Scout meeting orchestrated by a character named ‘Big Gay Al’.

The move has been met with some backlash, with calls to boycott the institution in the same way that Bud Light customers chose to stop supporting the company after they partnered with a transgender influencer.

‘Boy Scouts are removing the word boy from their name after 114 years. Now they will be called Scouting America,’ one irate X user wrote.

‘Bud light them too. Seriously, BUD LIGHT every piece of garbage institution in this country that is doing everything they can to tear down and torch our culture, our traditions, common sense, biology, and our way of life.’

‘”Everyone can be their authentic self and they will be welcomed here” This is antithetical to Boy Scouts,’ another fumed.

‘The boy is to be shaped by scouting, HE should change, that’s the point. Not the other way around. This is little more than a humiliation ritual.’

Radio presenter Dana Loesch pointed out that a separate organization for Girl Scouts already exists.

JUST IN: The Boy Scouts have rebranded and are dropping the ‘Boy’ to become ‘Scouting America’ so “everyone feels welcome.”

South Park strikes again.

The woke organization says they want to be welcoming and inclusive which is why they are dropping the ‘boy.’

“This will be a… pic.twitter.com/SBXNvbbcpn

— Collin Rugg (@CollinRugg) May 7, 2024

The organization won’t officially become Scouting America until February 8, 2025, the organization’s 115th birthday. But Krone said he expects people will start immediately using the name.

-

Barron Trump to Step Into Political Arena as Florida Delegate at Republican Convention

11 hours ago • 2 min read • 8 Comments -

Georgia Court Agrees to Hear Appeal on Fani Willis Removal from Trump Case

20 hours ago • 3 min read • 14 Comments -

READ: Michael Avenatti Releases Scathing Statement in Response to Stormy Daniels Testimony Against Trump

11 hours ago • 4 min read • 4 Comments -

Illegal Migrants Won’t Leave Tent City, Send List of 13 Demands to Dem Mayor

11 hours ago • 2 min read • 20 Comments

WoW ! The Democrat’s/ Government just Wants EVERYONE TO DIE ! THEY WANT TO KILL 2/3 OF THE POPULATION ! NOBODY WANTS A BABY FROM A GODLESS FAG !

Sounds like more money for the abortionist. Woman’s health care at its finest. What a fuking joke!

What about blood donations?