Ukraine Front-Line Troops Getting Older: “Physically Can’t Handle”

-

WATCH: 13-Year-Old Girl Allegedly Mobbed by Parents, Beaten by Student at NY High School

-

Biden Tries to Downplay Age with Jokes, Mocks Trump at White House Correspondents Dinner

-

Hamas’ Sexual Violence Against Israeli Women Is Revealed in New Documentary, ‘Screams Before Silence’

-

Thousands of Islamists Rally for Caliphate in Germany

During a break from fighting the Russians, an avuncular rifleman recalled how he was going for a haircut one day when he was press-ganged into joining the Ukrainian army, WSJ reported.

Three recruitment officials accosted the stocky, gray-haired 47-year-old outside the barber shop in his small hometown, ordered him to get in a car and detained him for two days in a dark room at the local draft center until he had signed up.

“I got my haircut at the training camp,” he said.

Now known by his military call sign Dubok, the former electrical engineer offered to serve as a technician in the rear. “But to get that job, you have to pay bribes,” he said. Instead, he was sent to join an infantry unit depleted by months of hard fighting. His battalion of the 47th Mechanized Brigade is defending the city of Avdiivka against waves of Russian assaults, the biggest current battle in Russia’s relentless war on Ukraine.

“Physically, I can’t handle this,” Dubok said of front-line combat. “I’m deeply disappointed that I’m no longer 20.”

Ukraine needs to rebuild its battered army. The infantry, which bears the brunt of deaths and injuries, is chronically short of men after nearly two years of resisting Russia’s full-blown invasion.

The most highly motivated fighters volunteered early. Those who haven’t been killed or wounded often say they are exhausted. Ukraine now relies on the draft—and sometimes on rounding up men—to replenish the ranks. Meanwhile, Russia can draw on a much larger population to replace its own heavy losses.

But a rickety draft system isn’t mobilizing Ukraine’s manpower effectively, providing the quantity and quality of troops needed, or sharing the burden fairly across Ukrainian society, say many soldiers and military analysts.

A combination of corruption, exemptions and political caution has protected much of Ukraine’s urban middle class against having to fight in the cold and muddy trenches. On the long front line, a disproportionate share of draftees are middle-aged men like Dubok. Often they are from villages and small towns and were too poor to buy their way out.

Veteran soldiers who have been fighting since 2022—some since 2014, when Russia first invaded Ukraine’s east—express frustration that new recruits are often past their physical prime.

“The quality of the replacements is not good. They’re rural guys aged 43 to 50, sometimes with health problems,” said an experienced infantryman fighting near Avdiivka.

Tired fighters note bitterly that when they go on leave in big cities such as Kyiv or Dnipro, they see able-bodied men in their 20s and 30s frequenting gyms, bars and hip restaurants.

“We don’t have full-on mobilization” of society, said a drone operator with the Ukrainian Navy’s special forces, known by his call sign Dobro. “But it’s a necessity. We can’t do without it.”

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said on Tuesday that the military was asking him for up to 500,000 more troops. He said no decision has been taken, calling the issue “very sensitive.” He noted that many soldiers who have been fighting a long time will also need to be demobilized at some point.

Dubok, the 47-year-old, didn’t protest or resist when he was detained at the draft center. “I went to school with the guys who processed me. I didn’t want to create problems for them,” he said. He had been thinking about joining the military anyway. “But not this way,” he said.

The day Dubok was drafted, his wife was left waiting for him at home with strawberries and cream. Now he watches rats feasting on dead bodies in the muddy battlefield around Avdiivka. “I’ve never seen such big rats in my life,” he said.

Stories of men being confronted in the street and detained by draft officials abound in Ukraine. Some incidents have been filmed and put on the internet. “It’s unlawful. They can only hand out draft notices, not detain people,” said Serhiy Parokhnenko, a lawyer from Dnipro whose clients include men challenging their call-up.

A Defense Ministry official admitted violations by some local recruitment staff but said too many citizens are ignoring their army summons.

Finding willing recruits for the infantry is proving especially difficult in the current phase of attritional warfare. The West’s fading support for Ukraine is darkening the country’s mood, and making front-line combat even more daunting.

Growing Republican opposition in Congress has held up U.S. military and financial aid. European Union aid is being impeded by Hungary, whose leader Viktor Orban has long had warm relations with Moscow.

Western deliveries of arms and ammunition have slowed sharply. Russia has regained a clear advantage in artillery firepower, where Ukraine had parity earlier this year.

About 800,000 people serve in Ukraine’s armed forces, Defense Minister Rustem Umerov said recently. Casualties in the war are a tightly held secret, but full hospitals and graveyards around Ukraine show the high price the country is paying to defy Russia’s attempted conquest.

On paper, Ukraine still has a large reserve of potential manpower, with several million male residents in their 20s and 30s who have yet to fight. The military hasn’t drafted men under the age of 27 so far, although Parliament has authorized a lower age limit of 25. Groups exempt from the draft include fathers of several children, carers for disabled people and workers in key sectors.

News

DeSantis and Trump Meet Privately for Several Hours in Miami

Former President Trump and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis met privately in Miami on Sunday, multiple Republicans with knowledge of the meeting confirmed to Fox News.

During the several-hour meeting, DeSantis agreed to help Trump as the GOP’s presumptive presidential nominee tries to close his fundraising gap with President Biden in their 2024 election rematch, the sources confirmed.

DeSantis, who was convincingly re-elected in 2022 before launching an unsuccessful bid for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination, has built up a formidable network of wealthy donors who could be helpful to Trump as the general election campaign heats up.

News of the meeting was first reported by the Washington Post, which said the get-together between the two rivals was orchestrated by Steve Witkoff, a Florida real estate broker known to both Trump and DeSantis.

Sources familiar confirmed to Fox News that the meeting was set up nearly 10 days ago, after DeSantis approached Witkoff.

The meeting appears to be the first time DeSantis and Trump have spoken, let alone met in person, since the governor ended his White House bid in January after a disappointing second-place finish in the Iowa caucuses, far behind Trump.

The former president and his allies spent nearly a year attacking DeSantis as the two squared off for the GOP nomination that also included other contenders.

DeSantis suspended his presidential campaign just two days ahead of the New Hampshire primary and has since endorsed Trump. But to date, DeSantis hasn’t campaigned on Trump’s behalf.

During a February call with supporters, the governor took aim at Trump and his top political advisers.

“I think he’s got people in his inner circle who were part of our orbit years ago that we fired, and I think some of that is they just have an ax to grind,” DeSantis said at the time.

In response, top Trump campaign aide Chris LaCivita called DeSantis a “sad little man.”

While many on Trump’s team and his wider political orbit detest DeSantis, the former president may be more forgiving if it benefits him.

Trump said in January after DeSantis endorsed him that he would “officially retire” the derogatory “Ron DeSanctimonious” nickname he used repeatedly to attack the Florida governor for nearly a year.

News

Oklahoma Tornadoes Kill 4; State of Emergency Issued

Tornadoes killed four people in Oklahoma and left thousands without power Sunday after a destructive outbreak of severe weather flattened buildings in the heart of one rural town and injured at least 100 people across the state.

More than 20,000 people remained without electricity after tornadoes began late Saturday night. The destruction was extensive in Sulphur, a town of about 5,000 people, where a tornado crumpled many downtown buildings, tossed cars and buses and sheared the roofs off houses across a 15-block radius.

“You just can’t believe the destruction,” Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt said during a visit to the hard-hit town. “It seems like every business downtown has been destroyed.”

Stitt said about 30 people were injured alone in Sulphur, including some who were in a bar as the tornado struck. Hospitals across the state reported about 100 injuries, including people apparently cut or struck by debris or hurt from falls, according to the Oklahoma Department of Emergency Management.

White House officials said President Joe Biden spoke to Gov. Stitt on Sunday and offered the full support of the federal government.

The deadly weather in Oklahoma added to the dozens of reported tornadoes that wreaked havoc in the nation’s midsection since Friday. On Sunday, authorities in Iowa said a man injured during a tornado that hit the town of Minden on Friday had died, according to local reports.

Authorities said the tornado in Sulphur began in a city park before barreling through the downtown, flipping cars and ripping the roofs and walls off of brick buildings. Windows and doors were blown out of structures that remained standing.

“How do you rebuild it? This is complete devastation,” said Kelly Trussell, a lifelong Sulphur resident as she surveyed the damage. “It is crazy, you want to help but where do you start?”

Carolyn Goodman traveled to Sulphur from the nearby town of Ada in search of her former sister-in-law, who Goodman said was at a local bar before just before the tornado hit the area. Stitt said one of the victims was found inside a bar but authorities had not yet identified those killed.

“The bar was destroyed,” Goodman said. “I know they probably won’t find her alive … but I hope she is still alive.”

Farther north, a tornado near the town of Holdenville killed two people and damaged or destroyed more than a dozen homes, according to the Hughes County Emergency Medical Service. Another person was killed along Interstate 35 near the southern Oklahoma city of Marietta, state officials said.

Heavy rains that swept into Oklahoma with the tornadoes also caused dangerous flooding and water rescues. Outside Sulphur, rising lake levels shut down the Chickasaw National Recreation Area, where the storms wiped out a pedestrian bridge.

Stitt issued an executive order Sunday declaring a state of emergency in 12 counties due to the fallout from the severe weather.

At the Sulphur High School gym, where families took cover from the storm, Jackalyn Wright said she and her family heard what sounded like a helicopter as the tornado touched down over them.

Chad Smith, 43, said people ran into the gym as the wind picked up. The rain started coming faster and the doors slammed shut. “Just give me a beer and a lawn chair and I will sit outside and watch it,” Smith said. Instead, he took cover.

Residents in other states were also digging out from storm damage. A tornado in suburban Omaha, Nebraska, demolished homes and businesses Saturday as it moved for miles through farmland and into subdivisions, then slammed an Iowa town.

The tornado damage began Friday afternoon near Lincoln, Nebraska. An industrial building in Lancaster County was hit, causing it to collapse with 70 people inside. Several were trapped, but everyone was evacuated, and the three injuries were not life-threatening, authorities said.

One or possibly two tornadoes then spent around an hour creeping toward Omaha, leaving behind damage consistent with an EF3 twister, with winds of 135 to 165 mph (217 to 265 kph), said Chris Franks, a meteorologist in the National Weather Service’s Omaha office.

Nebraska Gov. Jim Pillen and Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds spent Saturday touring the damage and arranging for assistance for the damaged communities. Formal damage assessments are still underway, but the states plan to seek federal help.

News

Half Arrested at UT-Austin Pro-Palestinian Protest Not Affiliated with School

Nearly half of the pro-Palestinian protesters arrested earlier this week at The University of Texas at Austin were not affiliated with the university.

Law enforcement officials arrested 57 protesters during Wednesday’s event organized by the Palestine Solidarity Committee after participants refused to disperse despite demands from authorities and the university. Of those arrested, 26 were neither students nor faculty of the university, according to officials at UT-Austin.

Hundreds of students walked out of class Wednesday in support of Palestinians in Gaza in the midst of the Israel-Hamas war. The war broke out after Palestinian terror group Hamas launched a brutal attack on Israel on Oct. 7, which left 1,200 Israelis dead. Hamas is believed to still be holding 129 hostages from Israel.

The organizers wrote on Instagram that they aimed to follow “in the footsteps of our comrades at Columbia SJP, Rutgers-New Brunswick, Yale, and countless others,” with SJP referring to Students for Justice in Palestine.

The anti-Israel student group demanded that the university “divest from death.”

“Consistent with this broader movement that is impacting so many, problematic aspects of the planned protest were modeled after a national organization’s protest playbook,” UT–Austin President Jay Hartzell said in a campuswide message Thursday evening. “And notably, 26 of the 55 individuals arrested yesterday had no UT affiliation.”

Local news outlet KTBC-TV reported that one of its photojournalists was among those arrested during the clash between police and protesters. He was booked into the Travis County jail on a criminal trespassing charge.

By Thursday evening, all of those arrested had been released. The Travis County prosecutor said it had dropped all criminal trespassing charges, citing “deficiencies” in charging documents. Criminal trespassing is considered a misdemeanor in the state of Texas.

According to the Texas Tribune, the Texas Department of Public Safety has opened a criminal investigation into the arrest of the photojournalist.

The UT–Austin chapter of the American Association of University of Professors denounced Mr. Hartzell for allowing authorities to be deployed on campus during the class walkout.

“We, faculty of UT Austin, condemn President Jay Hartzell and our administrative leaders’ decision to invite city police as well as state troopers from across the state—on horses, motorcycles, and bicycles, in riot gear and armed with batons, pepper spray, tear gas and guns to our campus today in response to a planned peaceful event by our students,” read the statement posted on X on Wednesday night.

Policy Violation

Ahead of Wednesday’s demonstration, university officials warned the organizers that the event violated school policy and would not be allowed to take place in an effort to prevent the “pattern” that has occurred across the nation in recent weeks, leading to hundreds of arrests.

“The University’s decision to not allow yesterday’s event to go as planned was made because we had credible indications that the event’s organizers, whether national or local, were trying to follow the pattern we see elsewhere, using the apparatus of free speech and expression to severely disrupt a campus for a long period,” Mr. Hartzell continued.

Palestine Solidarity Committee (PSC) is a student organization with chapters at colleges and universities across the country.

The group’s website states that it is “dedicated to telling the story of the Palestinian struggle for justice and self-determination on the university campus and in the wider Austin community. We work to promote education, discourse, activism, and awareness of the Palestinian story through lectures by academics and political activists, movie screenings, and events and displays on the UT West Mall.”

The UT–Austin group, which holds biweekly meetings on campus, states under Article 1 of its bylaws that it will comply with school policies.

“This organization is a recognized student organization at The University of Texas at Austin and shall comply with all campus policies as set forth in the Institutional Rules on Student Services and Activities and Information on Students’ Rights and Responsibilities,” it says.

UT Suspends Organization

The university suspended the student group from campus after another walkout on Thursday, which was organized in part by the faculty group that condemned the university for enforcing its rules.

Police were present during Thursday’s peaceful event.

“Students and faculty affirmed their commitment to continue struggling for the liberation of Palestine, to demand their university divest, and demand the resignation of President Jay Hartzell for greenlighting the militarized brutality enforced on students,” PSC wrote on Instagram.

PSC has held more than a dozen pro-Palestinian events since October.

“I’m thankful we live in a country where free expression is a fiercely protected Constitutional right,” Mr. Hartzell said in his campuswide message on Thursday. “I’m grateful that our campus has seen 13 pro-Palestinian events take place during the past several months largely without incident—plus another one today. I am grateful that everyone is safe after yesterday, we continue to hold in-person classes, and that today’s events followed our long-standing campus standards for allowed demonstrations.”

Brian Davis, a spokesperson for the university, confirmed on Friday that the student group had been suspended from campus in the wake of this week’s events. The length of the suspension is not immediately clear. Mr. Davis said that the Dean of Students office would make that determination.

It is unknown whether any students have been reprimanded for the events that occurred earlier this week. That information is protected by federal privacy laws.

“I encourage us all to continue to communicate and work together, and to help our students finish this school year in positive, safe and celebratory ways,” Mr. Hartzell said.

News

Dan Rather Makes Return to CBS, 18 Years After Bitter Departure

Dan Rather returned to the CBS News airwaves for the first time since his bitter exit 18 years ago, appearing in a reflective interview on “CBS Sunday Morning” days before the debut of a Netflix documentary on the 92-year-old newsman’s life.

After 44 years at the network, 24 as anchor of the “CBS Evening News,” Rather left under a cloud following a botched investigation into then-President George W. Bush’s military record. Rather signed off as anchor for the last time on March 9, 2005, and exited the network when his contract ended 15 months later.

With continued enmity between him and since-deposed CBS chief Leslie Moonves, Rather essentially became a nonperson at the news division he dominated for decades.

“Without apology or explanation, I miss CBS,” Rather told correspondent Lee Cowan in the interview that aired Sunday. “I’ve missed it since the day I left.”

Rather escaped official blame for the report that questioned Bush’s Vietnam War-era National Guard service but, as the anchor who introduced it, was identified with it. CBS could not vouch for the authenticity of some documents upon which the report was based, although many people involved in the story still believe it was true.

In the documentary “Rather,” debuting Wednesday on Netflix, Rather said he thought he would survive the incident, but his wife, Jean, told him, “You got into a fight with the president of the United States during his reelection campaign. What did you think was going to happen?”

Rather did not retire after leaving CBS, doing investigative journalism and rock star interviews for HDNet, a digital cable and satellite television network. Over the past few years, he has become known to a new generation as a tart-talking presence on social media.

This past week, he posted on X during former President Trump’s hush-money trial: “Is it just me or did today seem sleazy even for Donald Trump?”

“You either get engaged and you get engaged in the new terms … or you’re out of the game,” Rather said in the CBS interview, filmed at his home in Texas. “And I wanted to stay in the game.”

The Netflix documentary traces his career from coverage of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, the Vietnam War and Watergate, through his anchor years and beyond. It includes some of the then tightly-wound Rather’s odder incidents, including an assault in New York City by someone saying, “What’s the frequency, Kenneth,” then later appearing onstage with R.E.M. when the group performed its song of the same name.

In both the documentary and in the CBS interview, Rather bypasses his career when talk turned to his legacy.

“In the end, whatever remains of one’s life — family, friends — those are going to be the things for which you’re remembered,” he said.

News

Russia Arrests More Journalists on ‘Extremism’ Charges

Three Russian journalists were arrested Friday and Saturday and detained, as Russia continues a crackdown on media inside the country.

Konstantin Gabov and Sergey Karelin were charged with “extremism” on Saturday, The Associated Press (AP) first reported. They stand accused of working with a political group associated with the late Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, who died earlier this year in prison.

The pair will be held in custody for at least two months before trial. The charges carry a sentence of two to six years in prison, if convicted.

Forbes Russia journalist Sergei Mingazov was also arrested Friday, his lawyer told the AP, on charges of spreading misinformation. Prosecutors said he was jailed for reporting about alleged Russian war crimes in the Ukrainian city of Bucha.

The three journalists jailed in recent days are all Russian citizens. Karelin holds dual Israeli citizenship, and previously worked as a cameraman for the AP and the German outlet Deutsche Welle.

“The Associated Press is very concerned by the detention of Russian video journalist Sergey Karelin,” the AP said in a statement. “We are seeking additional information.”

Mingazov worked as a freelance reporter for Reuters, Deutsche Welle and other outlets.

Russian prosecutors said the two reporters worked with the Anti-Corruption Foundation, a watchdog group associated with Navalny’s political opposition. Russian critics and the U.S. government have accused Russian leaders of being responsible for Navalny’s death.

The arrests come as the Russian government cracks down on dissent as the invasion of Ukraine drags into a third year. In the wake of the war, the government has passed laws criminalizing what it deems false information about the military, or statements seen as discrediting the military, effectively outlawing any criticism of the war in Ukraine or speech that deviates from the official narrative.

Among the journalists detained in Russia is an American, The Wall Street Journal’s Evan Gershkovich. Gershkovich marked one year in prison last month, charged with espionage. The Journal and State Department have blasted the charges as false, and the Biden administration has committed to pursing a prisoner exchange to free him.

Gershkovich has yet to face trial and will remain in custody pending a trial until at least June.

News

Taylor Swift Flew 178,000 Miles in Year — Equivalent to Seven Times Around World!

Taylor Swift’s private jet tracker has revealed he’s heard nothing since the star’s legal team sent a cease and desist letter to stop him from “stalking” her online.

Computer student Jack Sweeney remains defiant and kept on posting the whereabouts of the singer’s two private jets, although she sold one earlier this year.

The 21-year-old has doubled down on releasing flight data, and this month released a YouTube video of all of Taylor’s flights from 2023, which would be enough to fly around the globe seven times.

He hasn’t counted how many there are but was told it’s over 170 flights.

The video concludes with the info that “Swift’s two private jets flew 178,000 miles in 2023 equivalent to flying around the earth 7 times. emitting ~ 1200 tons of C02 in the process. That’s 83 times the average American.”

He added a direct Taylor quote, “Jet lag is a choice.”

It was a comment the star made after flying from Tokyo to Las Vegas to watch boyfriend Travis Kelce win the Super Bowl.

Jack – a junior at the University of Central Florida – has faced unprecedented scrutiny after Taylor, 34, sent a “cease and desist letter” on December 22 claiming that he was assisting stalkers.

“While this may be a game to you, or an avenue that you hope will earn you wealth or fame, it is a life-or-death matter for our Client,” the letter read.

“Ms Swift has dealt with stalkers and other individuals who wish her harm since she was a teenager… the reality has forced our Client to live her life in a constant state of fear for her personal safety.”

Her spokesperson went one step further and said Jack’s dedicated Instagram account to Taylor’s jet had a “connection” to a man being arrested in January outside her townhouse in Manhattan.

Yet, four months on, Jack has heard nothing from Taylor’s lawyers – nor does he believe he ever will.

Taylor’s team was successful in getting Jack’s dedicated Swift Jets Instagram page shut down, and he’s not been able to restart it.

He says it’s just like in 2022 when Elon Musk, who also publicly slammed Jack for tracking his jet on his own platform X, offered $5,000 for him to stop, but Jack refused.

‘INTIMIDATING’

“Nothing [has happened]. I’m not really surprised,” Jack said.

“It’s pretty much like with Elon, you know, they’ll say something to intimidate the smaller person.

“It’s the attention they’re getting that they don’t like.”

“I like it – that it brings awareness,” Jack added.

He says that exposing the amount Taylor used the jet in 2023 – and also having other Instagram accounts dedicated to celebs such as Kylie Jenner and Kim Kardashian – shouldn’t be seen as a “competition.”

In fact, Taylor does not even make the top 10 when it comes to celebrities’ private jet use – the top three are rapper Travis Scott, Kim K, and Musk himself.

JET GROUNDED?

Nevertheless, it’s an uncanny coincidence that Jack says Taylor’s private jet has barely been used since the story made the headlines in December, preferring to take charter planes so that it’s more difficult for spotters to track.

“There’s so many people, it’s not really a competition for who’s the biggest polluter,” he said.

“The one jet [of Taylor’s] that is used is maybe every couple of weeks now just between Tennessee and California. Since this new year, she’s not always used the jet for tour dates.

“It could be that reason [of negative publicity], or it could be that the charter jet is nicer, a bit faster, and can go further.”

Jack says that if Taylor continues to hire charters for the European leg of her tour, which kicks off next month, it won’t be difficult to know who it is.

“If it’s just in two locations where it’s Nashville and some European location, how many people are leaving Nashville [for Europe] on a charter?” he said.

“Most people, even without me, are doing it now, there’s people posting on Reddit.”

He is now working on a video of all of Musk’s flights last year and said the Tesla founder will “probably not” be too pleased when he posts it on X.

News

Ford Lost $130,000 on Every EV It Sold, Delays Plans to Make More

Ford Motor Company reported a whopping $132,000 loss on each electric vehicle (EV) sold during the first three months of 2024, amassing a $1.3 billion loss.

The auto manufacturer’s electric vehicle unit revealed Thursday that they experienced a 20 percent decrease in sales volume and were forced to slash prices due to low consumer demand, CNN reported.

The revenue for Ford’s EV car, the Model e, plunged by 84 percent to about $100 million, which the company blamed on EV price cuts across the auto industry.

“That resulted in the $1.3 billion loss before interest and taxes (EBIT), and the massive per-vehicle loss in the Model e unit,” the publication noted.

The recent figures are part of a trend of loss for Ford, with their Model e reporting a full-year EBIT loss of $4.7 billion on the sale of 116,000 units. This is an average loss of $40,525 per vehicle — and even that is just a third of the per-vehicle loss seen in the first three months of 2024.

Now, company officials are estimating that their EV division will lose a grand total of $5 billion this year, up from $4.7 billion last year.

“Americans don’t want EVs at levels Biden’s climate hysteria require,” author and businessman Andy Puzder wrote on X. “Ford’s EV Q1 losses soared to $1.3 billion — a ridiculous $132,000 per EV sold. All Ford’s profits came from combustion engine vehicle sales. Collectivist policies destroy prosperity.”

Americans don’t want EVs at levels Biden’s climate hysteria require. Ford’s EV Q1 losses soared to $1.3 billion – a ridiculous $132,000 per EV sold. All Ford’s profits came from combustion engine vehicle sales. Collectivist policies destroy prosperity. https://t.co/U24fA4YHTz

— Andy Puzder (@AndyPuzder) April 25, 2024

“This does not appear to be “sustainable,” said environmentalist Patrick Moore.

Ford reports for the first quarter they lost $132,000 on every EV sold. This does not appear to be “sustainable”.https://t.co/1dKe4T2jcd

— Patrick Moore (@EcoSenseNow) April 28, 2024

Energy and environmental science expert Steve Milloy called Ford’s loss a “massive EV disaster.”

Massive EV disaster:

Ford lost $132,000 on every EV sold in the first quarter of this year.https://t.co/NK658JiY09 pic.twitter.com/BAZ80l6zZm

— Steve Milloy (@JunkScience) April 27, 2024

Ford announced earlier this month that the company will delay producing two new electric models, opting for hybrid vehicles instead.

“Many companies rushed in too fast with E.V.s that were too expensive and there was not as much of a market for them as they thought,” Sam Abuelsamid, transportation and mobility analyst at research firm Guidehouse Insights, told the New York Times. “That’s made it a lot tougher to sell those vehicles.”

News

WATCH: 13-Year-Old Girl Allegedly Mobbed by Parents, Beaten by Student at NY High School

A 13-year-old Montessori student was mobbed by a group of parents as they egged on a classmate beating the teen — a horrifying incident caught on video last week outside the Yonkers school, legal papers claim.

Now the teenager’s mother, Alenna Merritt, has pulled her daughter out of Yonkers Montessori Academy and filed a legal notice of claim alerting the city of Yonkers that she plans to sue for $40 million over the alleged negligent supervision.

“I felt confused and scared — they kept yelling in my face,” the teen told The Post during a phone interview with her, her mother and lawyer. “When I got attacked, I was feeling alone and scared because nobody was there to help me.”

Merritt’s daughter, whose name is being withheld at the family’s request and will be referred to by her initials, E.W., was swarmed by four parents and a grandparent of other students on the baseball field on school grounds at the pre-K-12 Montessori at 7:20 a.m. April 18, according to the mother, the claim and video footage from three phones.

The family’s lawyer, Mark Shirian, said it appeared from the video that the group was looking for E.W.’s friend for some reason and because the pal wasn’t there, it was a guilt-by-association situation, and they went after E.W. instead.

The parents can be heard in the footage yelling and swearing at E.W. before another student rushes her and starts slapping and pummeling her while the parents look on and E.W. attempts to defend herself by slapping back.

E.W. “was left unsupervised” and “violently assaulted on the premises of Yonkers Montessori Academy by students and parents and relatives of current students, during school hours,” according to the notice of claim filed Thursday with the city of Yonkers.

The teen “was viciously assaulted, beaten, and as a result has sustained severe physical, emotional, and psychological injuries,” reads the document, the legal precursor to filing a lawsuit against a municipal agency.

Merritt, 42, of Yonkers told The Post that she is pressing charges against the adults involved, also. She said that after reviewing cell-phone videos with the cops, who were called to school that day, the police were able to see that some of the adults also attacked her daughter and have issued a warrant for the arrest of at least one of them.

A joint rep for the Yonkers Police Department and Yonkers Public Schools confirmed that police issued an arrest warrant for Nancy Rosa, 55, on charges of third-degree assault, second-degree harassment and endangering the welfare of a child.

Rosa does not work for the schools, the representative said.

The investigation is ongoing, the rep said, declining to comment on whether further arrests could be expected.

Merritt said that when she got the call from her daughter around 7:30 a.m. that day, shortly after sending her off to school on the bus, she was “horrified” that this could have happened to her kid.

“I had my child screaming on the phone, screaming that she was hit … and I couldn’t even fathom it,” said Merritt, an executive director at a daycare center.

Merritt said her daughter is now receiving schooling remotely from a tutor — in a program provided by the Yonkers Montessori Academy — for the last roughly 40 days of the school year, since the mom said she wouldn’t dream of returning E.W. to the school, fearing for her safety.

E.W. has already been accepted to a private all-girls catholic school for the next school year.

Merritt filed a prior notice of claim against the same school in January alleging that staff sexually harassed E.W. by asking her to pull her bra and shake her breasts — believing she was hiding a vape on her person, the claim papers show.

Merritt said that with this second incident, she thought, “Here we go again.

“We have children who are not being supervised and not being protected,” Merritt told The Post. “I’m not going to put her in harm’s way and put her in the lion’s den every day.”

Merritt and her lawyer Shirian said they wonder if school security and staffers intentionally did not intervene in last week’s fight in retaliation for the pending claim against the school.

Shirian said Merritt and her daughter are “rightfully traumatized by this ordeal” and called for the school to swiftly implement “decisive action to rectify this situation and to prevent such incidents from happening in the future.

“This egregious failure to ensure the safety of students is utterly unacceptable,” Shirian told The Post.

The lawyer said his clients may consider bringing legal action against the parents involved as well, but likely not until after the criminal investigation and any resulting criminal cases are over.

The latest notice of claim alleges negligent supervision, negligent hiring, negligent infliction of emotional distress and other related accusations against Yonkers, the Yonkers Board of Education and Yonkers Montessori Academy.

The older notice of claim names many of the same defendants.

News

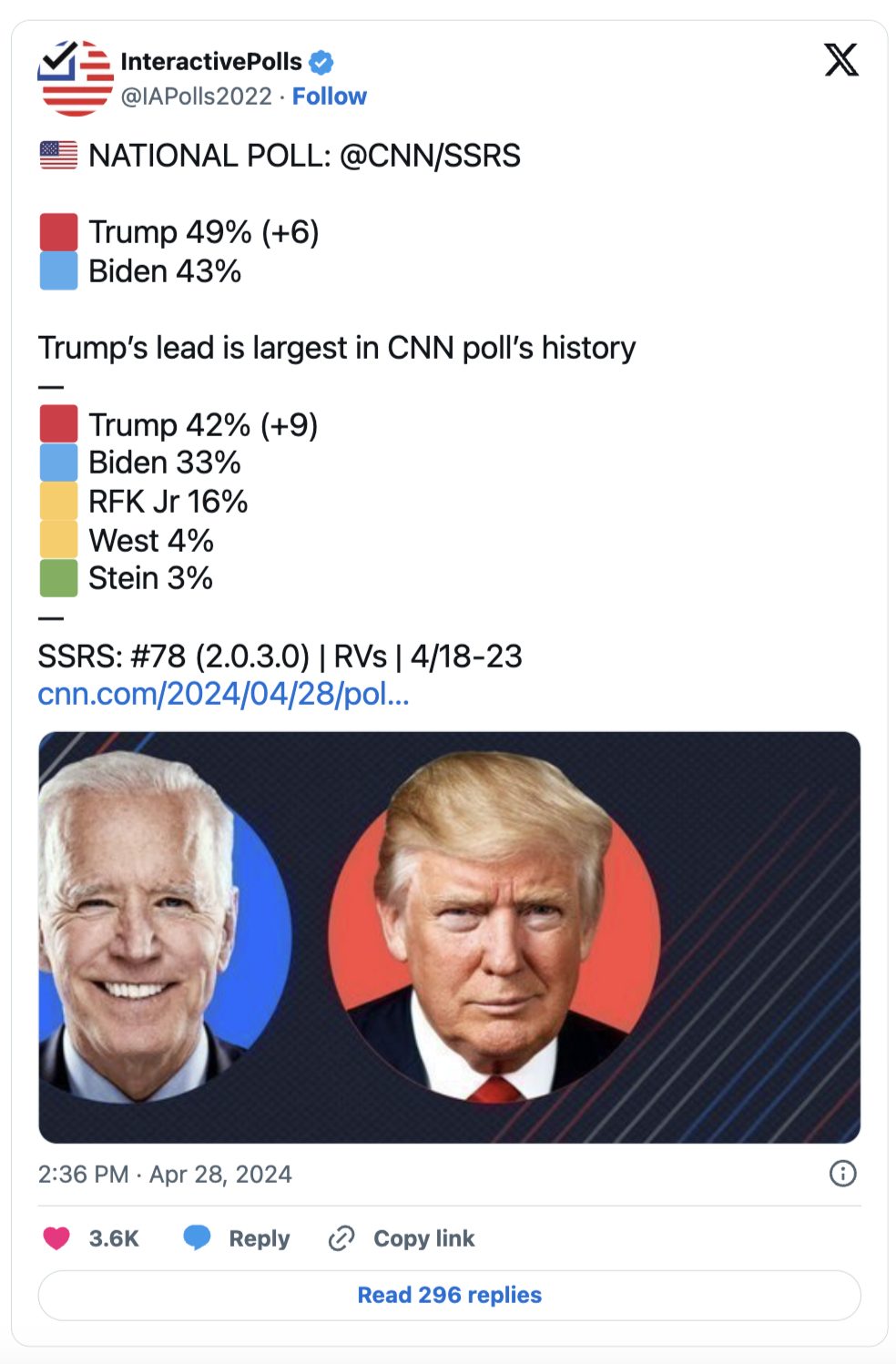

Trump Biggest Lead Ever Over Biden in CNN Poll

Former President Donald Trump has opened his biggest lead ever captured in the CNN poll of the American electorate, enjoying a six-point advantage over incumbent Democrat President Joe Biden.

Trump, at 49 percent, is six percent ahead of Biden’s 43 percent when the two are polled head-to-head.

When third-party candidates like Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Dr. Jill Stein, and Cornel West are added into the field, Trump’s lead over Biden grows to nearly double digits. In that multi-candidate scenario, Trump is at 42 percent, Biden is down at 33 percent, Kennedy is at 16 percent, West at four percent, and Stein at three percent.

That’s a nine percent lead for Trump nationally, an astounding number that if true would signal the former president is on track for an electoral college romp of Biden.

The CNN/SSRS poll was conducted from April 18 to April 23, and surveyed 1,212 American adults, including 967 registered voters, and has a margin of error of 3.4 percent for the full sample and 3.8 percent among registered voters. The numbers for the presidential race are from the registered voters sample.

CNN, in its story about the poll, found most Americans look back on Trump’s presidency positively—and look at Biden’s presidency negatively. CNN’s Jennifer Agiesta wrote that “in the coming rematch, opinions about the first term of each man vying for a second four years in the White House now appear to work in Trump’s favor, with most Americans saying that, looking back, Trump’s term as president was a success, while a broad majority says Biden’s has so far been a failure.”

“Looking back, 55% of all Americans now say they see Trump’s presidency as a success, while 44% see it as a failure. In a January 2021 poll taken just before Trump left office and days after the January 6 attack on the US Capitol, 55% considered his time as president a failure,” Agiesta wrote.

“Assessing Biden’s time in office so far, 61% say his presidency thus far has been a failure, while 39% say it’s been a success. That’s narrowly worse than the 57% who called the first year of his administration a failure in January 2022, with 41% calling it a success.”

Biden’s approval ratings on key issues like the economy and inflation, 34 percent and 29 percent respectively, is abysmal and seems to be working against him harshly. “In the new poll, 65% of registered voters call the economy extremely important to their vote for president, compared with 40% who felt that way in early 2020 and 46% who said the same at roughly this point in 2016,” Agiesta wrote.

“Those voters who say the economy is deeply important break heavily for Trump in a matchup against Biden, 62% to 30%.”

The poll’s release comes two weeks into Trump’s trial in New York City at the hands of Democrat District Attorney Alvin Bragg, and right after Biden roasted Trump at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner on Saturday evening.

While Trump is mostly stuck in a New York City courtroom, the campaign continues and Trump has sought to take advantage of having to be in New York by meeting with union workers and doing things like visiting a bodega whose owner was famously attacked.

Biden, meanwhile, has expended most of his efforts on trying to shift the national conversation off the economy, immigration, and national security to abortion, visiting Florida in recent weeks to highlight a forthcoming Sunshine State ballot initiative on the matter.

News

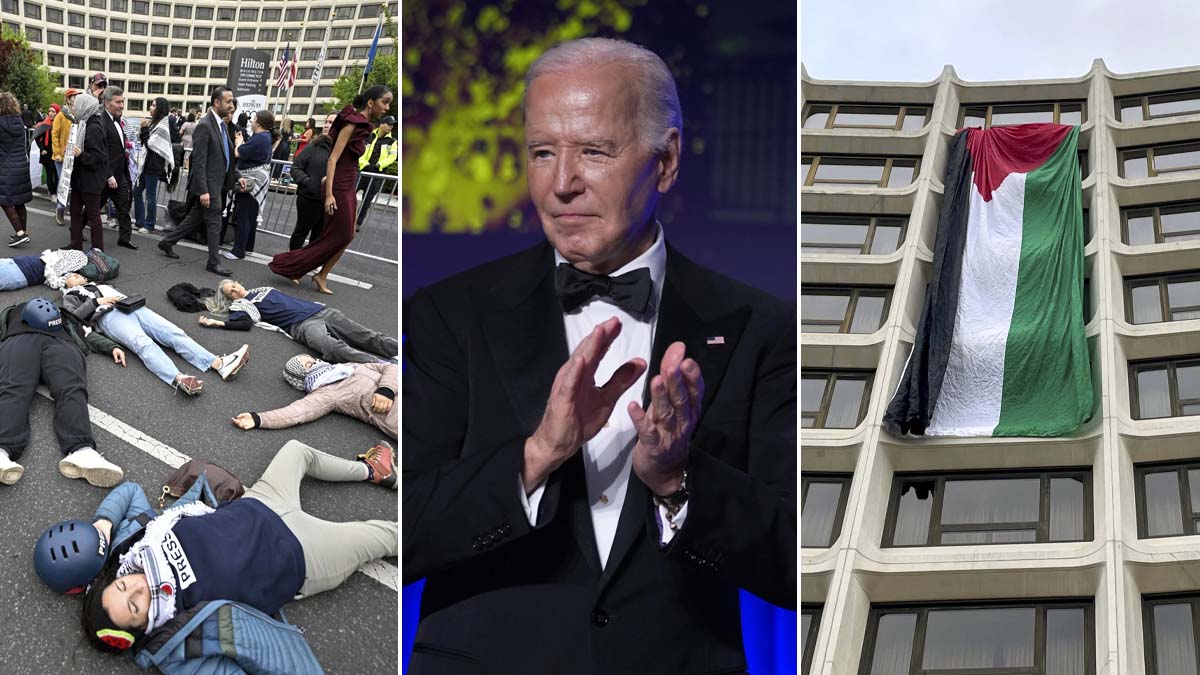

Biden Tries to Downplay Age with Jokes, Mocks Trump at White House Correspondents Dinner

President Biden took the stage at the annual White House Correspondents Dinner on Saturday and cracked jokes about his old age.

Biden spoke before a crowd of nearly 3,000 journalists, celebrities and Washington insiders at the Washington Hilton in Washington, D.C., as hundreds of anti-Israel protesters rallied outside.

The black-tie annual event gives Biden a major platform to speak to voters — and flex his sense of humor — while his approval rating sits at a historic low ahead of the November election.

Biden, 81, made jokes to make light of voters’ concerns about electing him into office for another four years in his advanced age.

“The 2024 election is in full swing. And yes. Age is an issue. I’m a grown man running against a 6-year-old,” the president quipped about his opponent, former President Donald Trump.

“I feel great, I really feel great,” he assured the crowd. “I’m campaigning all over the country. Pennsylvania, Georgia, North Carolina — I’ve always done well in the original 13 colonies.”

He also took some jabs at himself, saying that at last year’s dinner his wife told him she was nervous about his speech.

“I said to her ‘Don’t worry, it’s just like riding a bike. She said ‘that’s what I’m worried about’,” he joked about his infamous bike fall in Delaware in 2022.

Biden also took the offensive against Trump, poking fun at his strange, rambling speech in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in which he reminisced about the Civil War battle there.

“Trump’s speech was so embarrassing that the statue of Robert E Lee surrendered again,” Biden said.

“Age is the only thing we only have in common,” he said about himself and Trump, who is 77.

“My vice president actually endorses me,” he teased the former president for not receiving the endorsement of his vice president Mike Pence.

BREAKING: Biden attacks Trump at the White House Correspondents Dinner, says, “I’m a grown man running against a six-year-old.” says, “My vice president actually endorses me,” talks about “Stormy Weather.” WATCH pic.twitter.com/nfJ5ipjQsa

— Simon Ateba (@simonateba) April 28, 2024

Biden also lampooned the former president and his ongoing Stormy Daniels hush money trial in Manhattan: “Donald has had tough few days lately — you might call it stormy weather.”

“I’ve had a great stretch since the State of the Union. Donald has had a tough few days lately — you might call it stormy weather,” he said.

Biden also couldn’t resist going after Trump’s ego.

“Trump so desperately started reading those bibles he’s selling, then he got to the first commandment, ‘You should have no other God before me.’ That’s when he put it down and said this book’s not for me,” the president said.

Following Biden’s 10-minute speech, Saturday Night Live Weekend Update co-host Colin Jost roasted the president, politicians and media.

Jost did not hold back on making fun of Biden’s age.

After a photo of Jost from his high school days was shown on the screen, the comic said it’s not fair that Biden couldn’t be embarrassed with a high school photo “because the technology wasn’t invented yet.”

“I was excited to be up here on stage with President Biden tonight, mostly to see if I could figure out where Obama was pulling the strings from,” he joked.

“I got to be honest, It’s not easy following Biden. I mean it’s not easy following what he’s saying,” Jost added.

Trump also caught lots of flak from the SNL veteran.

“I also just wanted to point out, it’s 10 p.m. and Sleepy Joe is still awake, while Donald Trump has spent the last week falling asleep in court every morning,” Jost said.

Jost also cracked about his favorite hometown newspaper, The New York Post.

“Apologies to the New York Times, but as a Staten Islander, I get all my news from the New York Post. The only paper where the front page always has the same 200-point font, whether the headline is ‘World War Three to Start Tomorrow’ or ‘Central Park Owl Dead in Building Collision,’” the comic joked.

Ahead of Saturday’s event, Jeffrey Katzenberg, co-chair of Biden’s reelection campaign, reportedly held daily strategy sessions this week with his campaign team fine-tuning Biden’s comedy set, which was drafted by speechwriter Vinay Reddy, CNN reported.

Over several hours, including a four-hour session Friday night, Biden aides worked with the president to tweak his delivery and tone, according to the outlet.

One of the most pressing issues for the incumbent president going into the election is Israel’s war in Gaza, which has lost him vital support among left-leaning Democrats, imperiling his reelection prospects.

Hundreds of pro-Palestinian protesters gathered outside the Washington D.C. Hilton in force ahead of Saturday’s dinner, harassing the well-dressed guests as they walked into the event.

A massive Palestinian flag was draped over the side of the hotel, video shows. Other protesters stormed the red carpet as celebrities snapped photos behind them.

Palestinian supporters have repeatedly dubbed Biden “Genocide Joe” for his ongoing support for Israel’s war, which has left some 34,000 Gazans dead. He’s most recently come under fire this week for signing a $95 billion foreign aid package, which includes $26 billion for Israel.

The White House Correspondents Dinner raises money annually for scholarships for students looking to pursue a career in journalism.

At last year’s dinner, Biden promised to free Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich, who was arrested in Moscow on espionage charges last March.

This week, a full year later, a Moscow court rejected the journalist’s appeal to be released from pretrial detention, meaning the 32-year-old will remain behind bars until at least June 30.

Biden reiterated his vow to bring Gershkovich home, as his parents sat in the audience.

“We’re doing everything we can to bring home fellow journalists,” he said.

News

Kristi Noem’s VP Odds Crash After Dog Slaughtering Confession

After South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem admitted killing her dog and a family goat in her new book, her chances of becoming Donald Trump’s vice president have completely crashed, according to an online betting market.

On Polymarket, where gamblers can bet on just about anything under the sun, Noem’s self-admitted shooting of her 14-month-old wirehair pointer puppy has tanked her odds of being Trump’s running mate to just 4 percent, way down from the 10 percent chance she had just this Thursday, Newsweek reported.

Bettors think South Carolina Senator Tim Scott has the best shot – a 22 percent chance – at becoming Trump’s new right hand man, while New York congresswoman Elise Stefanik and Ohio Senator J.D. Vance – long considered potential favorites for the VP slot – are sitting at 9 percent and 6 percent, respectively.

This comes as President Joe Biden has recently overtaken the GOP’s assumed candidate Trump in the betting odds of who’ll win the election, with people favoring the Democrat by a little over a percentage point.

Noem explains in her forthcoming book that she gunned down her own animals to show she’s capable of dealing with anything that’s ‘difficult, messy and ugly.’

The book, titled No Going Back: The Truth on What’s Wrong with Politics and How We Move America Forward, will be released on May 7.

In her book, Noem writes about the dog, named Cricket, that she shot at the gravel pit on her family property, moments before her children came home from school.

The dog, Noem claimed, had an ‘aggressive personality’ that couldn’t be tamed – as evidenced by the fact that Cricket ruined a pheasant hunt for being ‘out of her mind with excitement, chasing all those birds and having the time of her life.’

Additionally when the South Dakota governor took Cricket with her to meet a local family the dog started killing the family’s chickens like ‘a trained assassin.’

According to a book excerpt obtained by the Guardian, Cricket ‘grabbed one chicken at a time, crunching it to death with one bite, then dropping it to attack another.’

When Noem finally grabbed the dog she wrote that Cricket ‘whipped around to bite me.’

Cricket was ‘the picture of pure joy.’ Meanwhile the chickens’ owner wept.

Noem said she wrote a check ‘for the price they asked, and helped them dispose of the carcasses littering the scene of the crime.’

‘I hated that dog,’ Noem wrote, believing the 14-month-old pooch to be ‘untrainable,’ ‘dangerous to anyone she came in conatct with’ and ‘less than worthless … as a hunting dog.’

So she decided to kill Cricket.

‘At that moment,’ the governor wrote. ‘I realized I had to put her down.’

She shot Cricket at the family’s gravel pit.

‘It was not a pleasant job,’ Noem said, ‘but it had to be done. And after it was over, I realized another unpleasant job needed to be done.’

Noem decided to off the family goat as well because he was ‘nasty and mean,’ as he remained uncastrated and smelled ‘disgusting, musky [and] rancid’ and ‘loved to chase’ the governor’s children.

She ‘dragged him to the gravel pit’ as well, but the goat jumped as she tried to shoot him, leaving him briefly alive.

Noem said she had to go back to her truck and retrieve another shell and then ‘hurried back to the gravel pit and put him down.’

Her actions were witnessed, she said, by a construction crew working nearby.

Moments later, the bus dropped off her kids.

‘Kennedy looked around confused,’ Noem recalled of her daughter, who asked, ‘Hey where’s Cricket?’

Noem then admitted, ‘I guess if I were a better politician I wouldn’t tell the story here.’

News

Green Party Presidential Candidate Jill Stein Arrested During Pro-Palestinian Protest

Green Party 2024 presidential candidate Jill Stein was arrested at Washington University in St. Louis during a pro-Palestinian protest Saturday.

Stein, her campaign manager Jason Call, and deputy campaign manager Kelly Merrill-Cayer were among the at least 80 protesters arrested at the campus encampment. Washington University’s protest is one of dozens unfolding across college campuses in the United States in recent days.

“The demand from the encampment was specifically for the university to divest from Boeing, which manufactures munitions used in the ongoing genocide against the Palestinian people in Gaza at their nearby St Charles facility,” Call said in a statement to the Washington Examiner.

“The Stein campaign supports the demands of the students and their peaceful protest and assembly on campus. Student protest for peace and civil liberties has always represented the best part of our collective moral conscience. Solidarity,” The statement said.

Washington University confirmed that more than 80 protesters were arrested, saying in a statement that “It quickly became clear through the words and actions of this group that they did not have good intentions on our campus and that this demonstration had the potential to get out of control and become dangerous. When the group began to set up a camp in violation of university policy, we made the decision to tell everyone present that they needed to leave.”

The statement continued, “All will face charges of trespassing and some may also be charged with resisting arrest and assault, including for injuries to police officers.”

According to her campaign, Stein was charged with assault, while Call and Merrill-Cayer were charged with criminal trespass.

BREAKING: Jill Stein and her Campaign Manager and Deputy Campaign Manager, Jason Call and Kelly Merrill-Cayer, have been arrested at Washington University in St. Louis while supporting a protest against WashU’s ties to the war on Gaza.

Video from @KallieECox pic.twitter.com/rkUYC9b5Qx— Dr. Jill Stein🌻 (@DrJillStein) April 28, 2024

According to one video, police used a bicycle to push against Stein and the other protesters. Stein called the use of force “shameful.”

This video shows police use of force against Jill and others at Washington University: https://t.co/wsFA5uocJi

— Dr. Jill Stein🌻 (@DrJillStein) April 28, 2024

Across the U.S., thousands of college students have set up encampments on their campuses, calling for a divestment from Israel, which has increased tensions on campus as some have turned anti-semitic.

The University of Southern California has canceled its main graduation ceremony due to campus unrest. At Columbia University, classes were moved to a hybrid format for the remainder of the semester.

News

Stunning New Forecast for U.S. National Debt

National debt is fast becoming the thorn in the side of the American economy that nobody wants to extract—and it will continue to cause damage, sending the U.S. into financial crisis and 10 years of stagnation.

That is increasingly the opinion of a growing number of experts who are sounding the alarm over the pace at which the U.S. government is gathering debt. More important, they fear this debt will mean the country will not be able to afford necessary borrowing in the future, in addition to the funds needed to service existing debt.

Among the ranks of those in the concerned camp are Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon, Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan, BlackRock CEO Larry Fink, and Wharton vice dean Joao Gomes.

Their outlook is evidenced by a March report from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). The CBO estimates that by 2054 public debt will represent 166% of GDP, reaching $141.1 trillion.

Currently the nation’s $34 trillion debt is approximately 99% of GDP and, according to the CBO, will steadily increase over the next 30 years. In the near term, the CBO expects debt as a percentage of GDP to exceed the record peak of the Second World War by 2029.

This mounting debt, the CBO writes, “would slow economic growth, push up interest payments to foreign holders of U.S. debt, and pose significant risks to the fiscal and economic outlook; it could also cause lawmakers to feel more constrained in their policy choices.”

The report goes on to add that the likelihood of a financial crisis is increasing as a result of growing debt, something which would cause interest rates to spike and, if paired with higher inflation, “could erode confidence in the U.S. dollar as the dominant international reserve currency.”

The outlook from the U.S. Government Accountability office (GAO) isn’t much better. A report released last month said the government is facing an “unsustainable” fiscal path that poses a “serious” threat to economic, security, and social issues if unaddressed.

The GAO advises Congress to make “difficult budgetary and policy decisions to address the key drivers of federal debt and change the government’s fiscal path,” adding: “The sooner actions are taken to change the long-term fiscal path, the less drastic they will need to be.”

As evidence of a fantastically complex fallout piles up, one might assume it will take an equally complicated approach to prevent it. Economists say that’s not the case—but that’s only if they believe it’s an issue at all. The hardest problem is precisely that: getting enough people to listen.

A sudden reckoning

Wharton’s Gomes has been making his concerns about the level of national debt known for some time now, and last week—following an interview with Fortune—he sat before the U.S. Senate Committee on the Budget and warned them of a train wreck ahead.

The vice dean of research at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School previously argued too few high-profile individuals were taking the matter seriously, but as an up-and-coming economist he felt compelled to step away from the pack to sound the alarm.

“The coming fiscal crisis will be triggered by a sudden loss of confidence by the general public in the federal government’s finances and on those tasked with managing them,” Gomes told chairman Sheldon Whitehouse and ranking member Chuck Grassley. “The projected path for the U.S. federal debt makes this … inevitable in the not too distant future.”

Among the fallouts from the crisis professor Gomes foresees is a sharp decline in the value of the dollar as interest rates spiral higher. He also believes inflation will spike as the government is forced to roll back on social programs to wrestle the deficit under control.

“These measures would have a further devastating effect in the economy, leading to a decade-long stagnation,” Gomes explained. “Given our projected demographic challenges, many older, and marginally attached, workers are likely to leave the labor force never to return again.”

‘Changing this future is not that difficult’

Professor Gomes outlines two well-known options to rebalance the variables: increase growth or cut spending. The former is by far the most preferable, Gomes said, but it wouldn’t accelerate quickly enough to do the job.

Even then, “the required fiscal correction is not drastic,” he added. “We certainly do not need to repay any part of the outstanding debt to prevent a crisis. In fact, government debt can continue to grow steadily over time without posing an immediate threat to the nation’s fiscal solvency—as long as the yearly deficits are not excessive.”

A fiscal adjustment of around 1.4% of GDP—or $400 billion—spread over two or three years would nip the issue in the bud, Gomes estimates.

However without a course correction a fiscal crisis is likely to occur in 2030, said Gomes, or as early as 2025 if the next administration rolls out an “expensive fiscal package that relies on implausibly rosy economic assumptions.”

Regardless, warns Gomes: “Its consequences will be severe and leave lasting—probably irreversible—scars on our economy and society.”

Redoing the math

Economists are increasingly revising the bill future generations will have to foot in order to pay for the fiscal outlays of governments way back when. However, that comes with a major caveat: a global pandemic.

For example, in 2019 the CBO projected U.S. public debt by 2049 would be 144% of GDP; by March’s estimate that figure stands at more than 150%.

However the ratio—and corresponding forecasted debt figure—does fluctuate depending on whom you ask. Even the CBO as recently as September 2023 projected the figure to be higher—estimating an 153% debt-to-GDP ratio by 2053.

The GAO puts debt at 200% of GDP by 2050, while the Penn Wharton Budget Model projects 190% of the size of the economy by the same year.

News

Hamas’ Sexual Violence Against Israeli Women Is Revealed in New Documentary, ‘Screams Before Silence’

Almost seven months after Hamas’ slaughter of 1,200 Israelis on October 7, a new documentary is set to be released that reveals the horrific atrocities and sexual assaults that took place that day.

Fox News Digital reported that former Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg’s documentary, “Screams Before Silence,” includes firsthand accounts of the horrible events that transpired on October 7, where over 1,000 Israelis were killed and 240 more taken as hostages back to Gaza.

“When you hear this chaos for like 20 minutes or 15 minutes, you understand that something much worse [is] happening right over there. It doesn’t stop. That was the the time when I started to be afraid I’m going to be raped,” a woman recalled from the Nova Music Festival attack.

Sandberg said that she decided to take on the project because “the world needs to see and acknowledge what happened.”

“After October 7th, the reports were coming out about not just mass murder, but mass sexual violence. And the usual people who should be speaking out were either ignoring it or denying it. And that’s not okay,” she continued.

The documentary takes viewers back to October 7, allowing them to hear from first responders and survivors who were on the ground.

Sandberg mentioned that the documentary will prove to viewers that Hamas members had deliberately set out to commit sexual violence against Israeli women.

In late 2023, Israeli actress Gal Gadot took to Instagram, sharing her thoughts on the matter, saying: “We claim we stand against rape, violence against women. We will not let women be victimized and then silenced. We say we believe women. Stand with women. Speak out for women.”

View this post on Instagram

“On October 7th, the world witnessed Hamas carrying out its violent plans in real time. Within hours of the October 7th attack, the first blood-chilling video emerged of Shani Louk being paraded naked and defiled by her proud assailants,” Gadot wrote on the social media platform, referring to Shani Louk, the German-Israeli tattoo artist who was kidnapped by Hamas.

Gadot continued: “Yet two months later women are still hostage to these rapists and the world has failed to call this situation what it is: an urgent emergency that demands a decisive response.”

“This is our moment as women and allies of women to act. I am beseeching all those who have done so much for women’s rights globally – from the UN, to the human rights community, to please join in the demand that Hamas release every single woman hostage immediately – not after the next round of international mediation, not after another day. These women cannot survive another moment of this horror.”

The documentary, in tandem with a thorough investigation carried out by the New York Times, seems to suggest that Hamas committed sexual assault many times on October 7. However, there are pro-Palestinian activists — many of which live in the U.S. — have denied that these sexual assaults actually took place.

News

Thousands of Islamists Rally for Caliphate in Germany

Some 1,000 protestors gathered in Hamburg’s Steindamm Street on Saturday, calling for an end to “dictatorship values,” according to the German daily Die Welt.

In a video posted on X, the crowd can be seen responding to shouts of ‘Takbir’ with “Allahu Akbar.” The video also shows the mob shouting part of the Shahada in Arabic, “There’s no God but God.” One demonstrator held a placard that read “Caliphate is the solution,” while others held signs with the inscription “Gaza has won the info war.”

Germany: “Kaliphate is the solution” poster at demonstration of the Islamist group “Muslim Interactive” in Hamburg.

— Azat Alsalem (@AzzatAlsaalem) April 28, 2024

The German daily newspaper noted the rally was organized by a group named “Muslim Interaktiv,” which also posted the video from the rally on its X account under the banner “Do not obey liars! Impressions from today’s demonstration in Hamburg.”

Behind Muslim Interaktiv

Die Welt further stated that according to the Hamburg Office for the Protection of the Constitution, the group is an extremist Islamist organization affiliated with the Hizb ut-Tahrir, a pan-Islamist, fundamentalist political organization that has for the purpose of the re-establishment of a caliphate. This political organization is banned from operating in Germany, as per the Hamburg office.

According to Ynet and German media, a leader of “Muslim Interaktiv” is the 25-year-old Joe Adade Boateng, also known as Raheem Boateng, who is studying education at the University of Hamburg.

He has a large presence on Instagram and TikTok, where he shares Islam-related content, targeting young Muslims in Germany.

Both he and “Muslim Interlaktiv” have addressed the Israel-Hamas war on social media. One joint post from December 2023 read, “Our main account has been blocked due to censorship surrounding the current genocide in Gaza. The government is trying to stop our activities using all possible means.”

News

Bishop Who Was Stabbed During Service Returns to Mass with Fiery Sermon

The Bishop who was stabbed in an alleged terror attack on the Christ the Good Shepherd Church in western Sydney has delivered a fiery sermon on his return to the pulpit, calling out Prime Minister Anthony Albanese in an impassioned defense of freedom of speech and religion.

Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel, carrying a gold cross and sporting a white eye patch after he suffered lacerations to his face in the alleged April 15 attack, said he could not “fathom” how freedom of speech could not be possible in a democratic country.

“I say to our beloved, the Australian government, and our beloved Prime Minister, the honorable Mr Albanese, I believe in one thing and that is the integrity and the identity of the human being,” he said.

“This human identity, this human integrity, is a God-given gift, no one else.

“Every human being has the right to their freedom of speech and freedom of religion.”

He said Buddhists, Hindus, Muslims and Atheists had the right to express their beliefs.

“Also the Christians have the right to express their beliefs, and for us to say, that free speech is dangerous, that free speech cannot be possible in a democratic country, I’m yet to fathom this. I’m yet to fathom this. We should be able as civilised human beings, as intellectuals, we should be able to criticise, to speak, and maybe, at some certain times, we may sound, or we may come across offensive to some degree, but we should be able to say, ‘I should not worry for my life to be exposed to threat or to be taken away’.

“A non Christian can criticize my faith, can attack my faith. I will say one thing, ‘may God forgive you, and may God bless you.

“This is a civilized way, an intellectual way, to approaching such events.

“But for us, to say that because of this freedom of speech, it is causing dramas and dilemmas, therefore everything should be censored, then where is democracy?

“Then where is humanity, where is integrity, where are the morals, where are the ethics, where are the principles, where are the values which the Western world, more so, have been fighting for human rights, which is the value of the human.”

A debate around the proper limits of free expression has erupted in the country in the wake of the alleged Wakeley terror attack.

A 16-year-old boy allegedly stabbed the bishop while he was giving a livestreamed sermon, with video of the violence quickly spreading online.

Australian eSafety commissioner Julie Inman Grant has ordered social media platform X, formerly known as Twitter, to take down certain posts commenting on the attack.

X’s Global Governance Affairs division has stated it will challenge the take-down order.

“This was a tragic event and we do not allow people to praise it or call for further violence,” X stated.

“There is a public conversation happening about the event, on X and across Australia, as is often the case when events of major public concern occur.

The recent attacks in Australia are a horrific assault on free society. Our condolences go out to those who have been affected, and we stand with the Australian people in calling for those responsible to be brought to justice.

Following these events, the Australian eSafety…

— Global Government Affairs (@GlobalAffairs) April 19, 2024

“While X respects the right of a country to enforce its laws within its jurisdiction, the eSafety Commissioner does not have the authority to dictate what content X’s users can see globally.

“We will robustly challenge this unlawful and dangerous approach in court.

“Global take-down orders go against the very principles of a free and open internet and threaten free speech everywhere.”

The bishop has come out in support of the company and the right of Australians to consume content linked to the attack.

Congregants of the Christ the Good Shepherd Church in Wakeley in western Sydney gasped and erupted into applause on Sunday evening as the Bishop returned to the pulpit to preach again following the alleged terror attack on him two weeks ago.

The Bishop appeared before the crowd as a curtain pulled apart on the church stage.

The crowd stood and clapped and cheered him as he appeared.

“May this holy and blessed day, the day of Hosanna, Palm Sunday according to the church calendar, may the Lord Jesus bless every Christian who is celebrating Palm Sunday today, and those who have celebrated it earlier,” he said to his followers.

“In Christ we are one.”

It was the Bishop’s first time back at the pulpit following the alleged April 15 terror attack, in which a 16-year-old boy allegedly stabbed the bishop while he was giving a livestreamed sermon, with video of the violence quickly spreading online.

The Bishop suffered lacerations to his face and body and paramedics took him to hospital for treatment.

On Sunday, he said “love never fails”, referencing a passage from the Bible.

“This is our Christian faith, but above all this is our Christ, who is all”

“And always taught to love one another, because God is love, and the Lord Jesus, he is God, revealed in the flesh, period.

“He taught us to love everyone, without any differentiation. This will never change.”

The Bishop also delivered a message to his alleged attacker.

“I’ll say it again, this young man who did this act, almost two weeks ago, I say to you, ‘my dear, you are my son and you will always be my son’,” the Bishop said.

“I will always pray for you, I will always wish you nothing but the best.

“And for whoever was in this act, in the name of my Jesus, I forgive you, I love you, and I will always pray for you.”

The Bishop offered sermons in both Arabic and English on Sunday.

News

Protesters Swarm White House Correspondents Dinner

Anti-Israel protesters swarmed the streets surrounding Saturday evening’s White House Correspondents’ Dinner, shouting at attendees and draping a massive Palestinian flag from one of the windows of the host hotel.

Associated Press reporter Farnoush Amiri commented on the crowds waiting outside the venue, saying that the scene before her was very different than it had been in years past.

“This is my third year covering the WHCD as the designated AP reporter for the WH pool and I’ve never seen anything like this,” she said of the gathered protesters. “President Biden’s motorcade will likely drive by these crowds shortly.”

This is my third year covering the WHCD as the designated AP reporter for the WH pool and I’ve never seen anything like this. President Biden’s motorcade will likely drive by these crowds shortly. https://t.co/ZnJjhCrmly

— Farnoush Amiri (@FarnoushAmiri) April 27, 2024

Amiri also noted that President Joe Biden’s motorcade took a different route to the event than it had in years past — and her assumption was that they were attempting to avoid the protests as much as possible.

In President Biden’s motorcade, which took a different route to the dinner than previous years, likely to avoid protesters. But some still were able to get through on the side streets. pic.twitter.com/3SmhH1YCFh

— Farnoush Amiri (@FarnoushAmiri) April 27, 2024

Protesters carried signs referencing journalists who have reportedly been killed in Gaza.

Scenes from outside the #WHCD where protesters are supporting a boycott called for by the colleagues of journalists killed in Gaza pic.twitter.com/J3kJZUYU3g

— nikki mccann ramírez (@NikkiMcR) April 27, 2024

Protesters attempted to surround attendees — among them Caitlyn Jenner — and confront them as they arrived, calling on journalists to boycott the event.

The protesters claimed they were there “to protest media complicity in genocide,” complaining that Palestinian journalists were being killed “with full U.S. backing” for reporting on the situation in Gaza.

Caitlyn Jenner confronted by protestors at White House Correspondents Dinner.

They’re here “to protest media complicity in genocide” & uplift calls from Palestinian journalists to boycott the event “as they are being targeted & killed for doing their jobs, with full US backing.” pic.twitter.com/OG7QLhl8zM

— Prem Thakker (@prem_thakker) April 27, 2024

“The pro-Hamas crowd has arrived outside the White House Correspondent’s Dinner and is VERY upset about me filming them,” Katie Pavlich posted.

The pro-Hamas crowd has arrived outside the White House Correspondent’s Dinner and is VERY upset about me filming them pic.twitter.com/xEg3a8EPDR

— Katie Pavlich (@KatiePavlich) April 27, 2024

The Palestinian flag, according to witnesses, was draped from a window of the Washington Hilton just before President Joe Biden was expected to arrive at the venue.

Demonstrators draped a massive Palestinian flag from the Washington Hilton just moments before POTUS is due for #WHCD pic.twitter.com/lbEnXlugcy

— Sean Langille (@SeanLangille) April 27, 2024

WUSA9 reporter Alexis Wainwright shared several videos of the protest, confirming that those present were calling for a boycott of the dinner.

Protests still happening right now outside of the White House Correspondents dinner at the Washington Hilton on Connecticut Ave NW.

They are calling for a boycott of this dinner. @wusa9 pic.twitter.com/M7VfYCiloo

— Alexis Wainwright (@AWainwrightTV) April 28, 2024

She also reported that at least one protester had been escorted away by police, prompting other protesters to yell at officers to let the person go.

Now other protesters have come over to call for police to let the person who’s been taken into custody go. pic.twitter.com/3oTHOSUu1K

— Alexis Wainwright (@AWainwrightTV) April 28, 2024

Ousted MSNBC host Mehdi Hasan publicly stated that despite attending the WHCD in the past, he would join with the anti-Israel protesters and sit this one out.

I have attended the White House Correspondents Dinner for the past two years. I decided not to attend today’s dinner (which, to be clear, is hosted by DC journalists not the White House) in solidarity with under-fire Palestinian journalists in Gaza who have called for a boycott. https://t.co/HZ6v1m9RTq

— Mehdi Hasan (@mehdirhasan) April 27, 2024

News

Justice Thomas Raises Question About Legitimacy of Special Counsel’s Trump Investigation

Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas raised a question Thursday that goes to the heart of Special Counsel Jack Smith’s charges against former President Donald Trump.

The high court was considering Trump’s argument that he is immune from prosecution for actions he took while president, but another issue is whether Smith and the Office of Special Counsel have the authority to bring charges at all.

“Did you, in this litigation, challenge the appointment of special counsel?” Thomas asked Trump attorney John Sauer on Thursday during a nearly three-hour session at the Supreme Court.

Sauer replied that Trump’s attorneys had not raised that concern “directly” in the current Supreme Court case — in which justices are considering Trump’s arguments that presidential immunity precludes the prosecution of charges that the former president illegally sought to overturn the 2020 election.

Sauer told Thomas that, “we totally agree with the analysis provided by Attorney General Meese [III] and Attorney General Mukasey.”

“It points to a very important issue here because one of [the special counsel’s] arguments is, of course, that we should have this presumption of regularity. That runs into the reality that we have here an extraordinary prosecutorial power being exercised by someone who was never nominated by the president or confirmed by the Senate at any time. So we agree with that position. We hadn’t raised it yet in this case when this case went up on appeal,” Sauer said.

In a 42-page amicus brief presented to the high court in March, Meese and Mukasey questioned whether “Jack Smith has lawful authority to undertake the ‘criminal prosecution'” of Trump. Mukasey and Meese — both former U.S. attorneys general — said Smith and the Office of Special Counsel itself have no authority to prosecute, in part because he was never confirmed by the Senate to any position.

Federal prosecutions, “can be taken only by persons properly appointed as federal officers to properly created federal offices,” Meese and Mukasey argued. “But neither Smith nor the position of special counsel under which he purportedly acts meets those criteria. He wields tremendous power, effectively answerable to no one, by design. And that is a serious problem for the rule of law — whatever one may think of former President Trump or the conduct on January 6, 2021, that Smith challenges in the underlying case.”

The crux of the problem, according to Meese, is that Smith was never confirmed by the Senate as a U.S. attorney, and no other statute allows the U.S. attorney general to name merely anyone as special counsel. Smith was acting U.S. attorney for a federal district in Tennessee in 2017, but he was never nominated to the position. He resigned from the private sector after then-President Trump nominated a different prosecutor as U.S. attorney for the middle district of Tennessee.

Meese and Mukasey argued that because the special counsel exercises broad authority to convene grand juries and make prosecutorial decisions, independent of the White House or the attorney general, he is far more powerful than any government officer who has not been confirmed by the Senate.

Sauer and Trump’s other attorneys objected to the legitimacy of Smith’s appointment in the charges against Trump in the classified documents case, also brought by Smith, before a Florida federal court.

In a March court filing in Florida, Trump’s attorneys claimed that the special counsel’s office argues in federal court that Smith is wholly independent of the White House and Garland — contradicting Trump’s arguments that the federal charges against him are politically motivated. But at the same time, the special counsel’s attorneys insist that Smith is subordinate to the attorney general, and therefore not subject to Senate confirmation under the Appointments Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

“There is significant tension between the Office’s assurances to that court that Smith is independent, and not prosecuting the Republican nominee for President at the direction of the Biden Administration, and the Office’s assurance here that Smith is not independent and is instead so thoroughly supervised and accountable to President Biden and Attorney General Garland that this Court should not be concerned about such tremendous power being exercised to alter the trajectory of the ongoing presidential election,” Trump’s attorneys wrote in the filing.